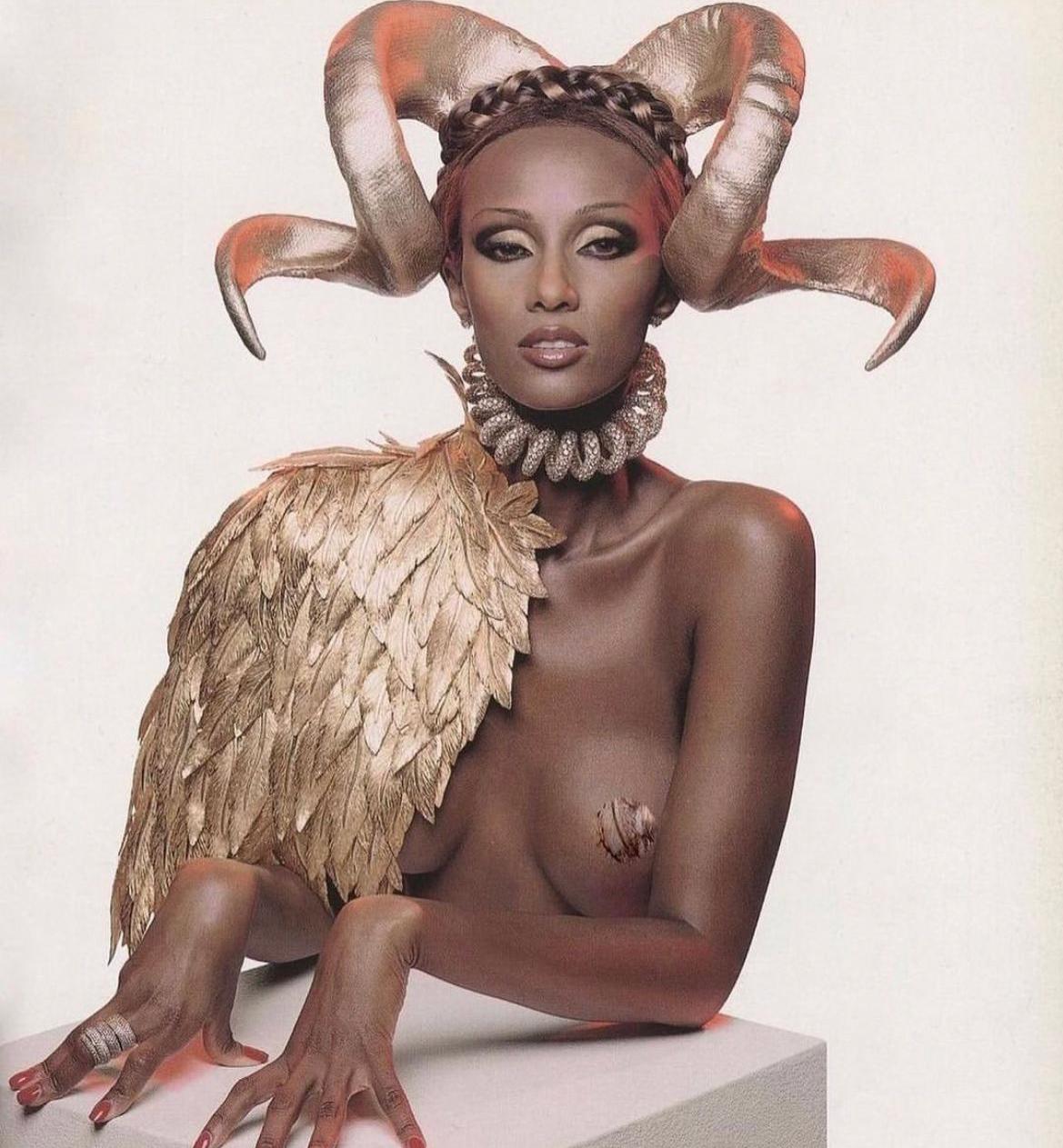

Iman by Inez and Vinoodh for Visionaire | Image courtesy of The Wall Group

Born in Detroit, Michigan, James Kaliardos was drawn to makeup from an early age. At just seven years old, he began doing his mother’s makeup, a moment of discovery for both of them when it became clear he had a natural talent. Inspired by the glamorous images of Francesco Scavullo and Richard Avedon and the unapologetic individuality of icons like Cher and Patti LaBelle, Kaliardos moved to New York to attend Parsons School of Design, where his creative path quickly accelerated. At Parsons, he became known as the go-to hairstylist and makeup artist in his dorm, but a pivotal turning point came when he attended a fashion symposium organized by his photography teacher. There, he met Bethann Hardison, Steven Meisel, and Helmut Newton—industry legends who would soon become mentors. “I don’t know if I would’ve pursued makeup without them,” Kaliardos reflects. “I never thought this would be my career, but when Steven Meisel says you’re good, you think, ‘Okay, maybe I won’t be a waiter after all.’”

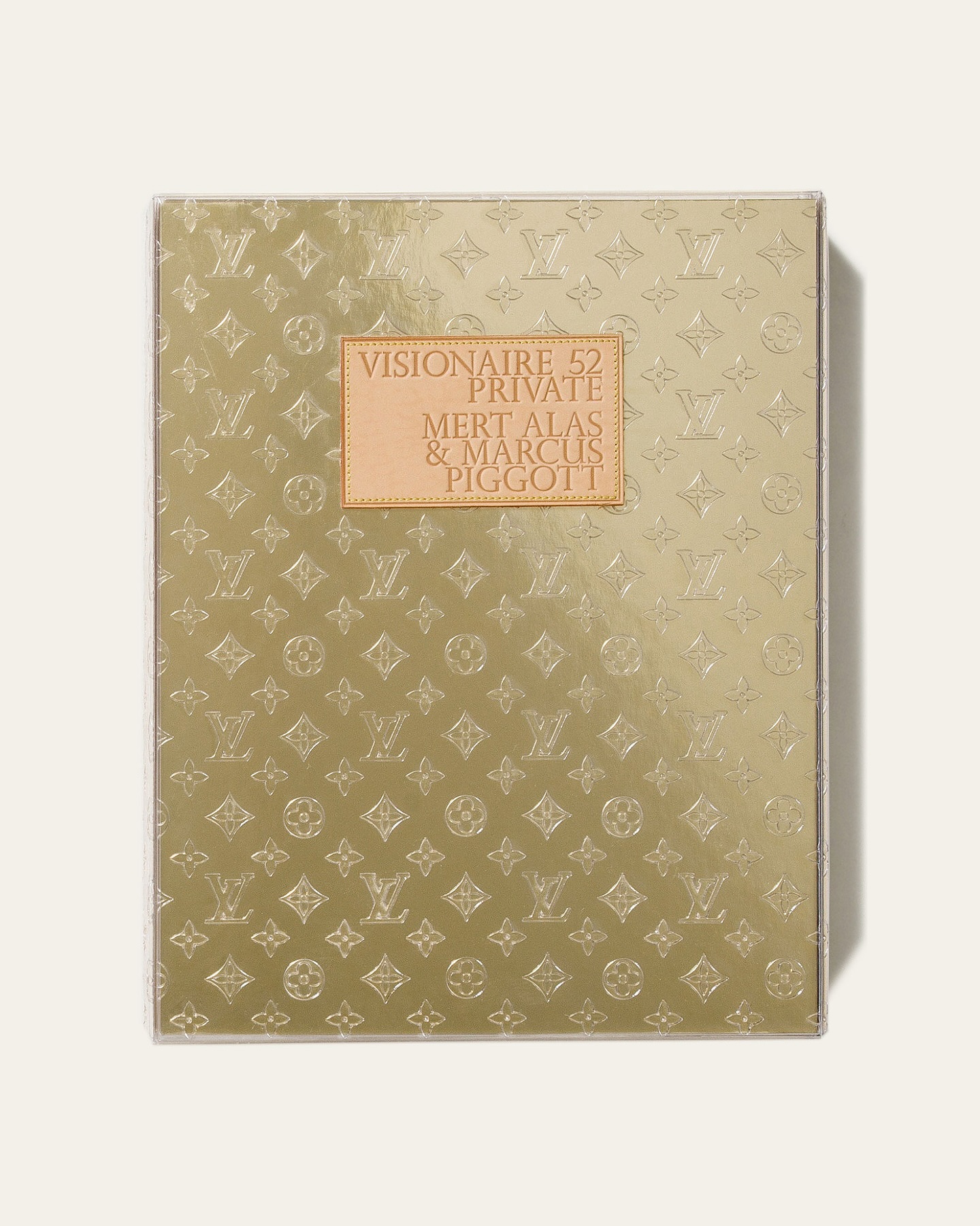

After building a name for himself in the world of beauty, Kaliardos, along with close friends Cecilia Dean and Stephen Gan, launched Visionaire in 1991. A boundary-pushing publication that merged art, fashion, and design, Visionaire quickly gained a cult following and became one of the most expensive and coveted magazines in the world. “Visionaire became this experimental space where artists felt safe trying something new, knowing it would be beautifully printed, surrounded by great work, and treated with care,” he explains. Over the years, Visionaire featured models like Iman, Naomi Campbell, and Devon Aoki, and collaborated with visionaries including Nick Knight, Karl Lagerfeld, and Mert Alas and Marcus Piggott. As more collaborators expressed a desire to create fashion-focused editorials, the team launched V Magazine. However, the shift to a commercially funded publication brought new challenges, particularly around advertiser demands. Today, he collaborates with artists like Miley Cyrus, whose latest project Something Beautiful he worked on closely with the beauty looks (and even made a special cameo), and powerhouses such as Nars Cosmetics, Tom Ford Beauty, and MAC. Also, a trained actor and writer, Kaliardos is now turning his attention to a new creative chapter. Models.com spoke with Kaliardos about the shifting definitions of beauty, from embracing individuality and imperfection to navigating today’s homogeneity.

Hunter Schafer by Richard Burbridge | Image courtesy of The Wall Group

Where are you from?

My parents are Greek, but I was born in Detroit, and then I also grew up in Grosse Pointe, a super conservative, completely white neighborhood right outside of Detroit. When I was growing up, you’d have potholes, and the lights would be out, and Detroit was just getting more and more in shambles. Then you’d hit Grosse Pointe, and it would be smooth roads and with beautiful trees and bushes that were manicured, it was very weird for me to grow up with that split. It was just was an odd place to grow up, but it taught me a lot. Whenever I say I’m from Detroit, people think it’s cool, and I love saying it. It has such an amazing musical history. There was something rebellious about it, you had to fight for your life in Detroit. My parents grew up there in the forties and fifties, so they saw the boom. I have always heard these incredible stories. My uncle was a trumpet player, and there were jazz clubs everywhere. They had one experience of the city, and our generation had a completely different one. The Detroit Institute of Arts was incredible, and the library was a great place, too. I used to sneak down there on the bus.

What first drew you to the world of beauty and fashion? Growing up in Detroit, were there specific cultural moments that helped you and your creativity?

It really started with my mother. She used to check out American Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar U.S. from the library because we couldn’t afford a subscription. You could keep them for two weeks, and during that time, I would pore over every page. I was completely drawn into the world of Francesco Scavullo and Richard Avedon, their images from the late ’70s and early ’80s had such power. What struck me most was how individual everyone looked. There was only one Cher, one Patti LaBelle. Each person had a distinct presence. I never imagined a world where people would want to look the same. That idea still feels strange to me. My mother looked a bit like Maria Callas. She was so gorgeous and wore cool eyeshadow and pale lips every day. I’d watch her get ready, and one day, I asked if I could try doing her makeup, and she said yes. Honestly, a star was born. I was just good at it right away. We both saw it. I was seven years old, using this purple eyeshadow palette, and she gently guided me with tips and suggestions. That intimacy, sharing a moment of beauty with my mother, stayed with me. I’ve tried to carry that same feeling into every job I do. Makeup, to me, is always a special moment. I want the person in my chair, woman, man, or whoever, to feel included in the process. I’m never just applying something to someone’s face. Especially with models, I make a point of making them feel like collaborators. They’re an essential part of the process. Models are often in this in-between space: not quite the client and not fully in control of the outcome. I’ve always empathized with that, being transformed into something else. To me, the best results happen when they’re involved in shaping that transformation. When they embody the look, they bring it to life. That’s always been my approach: it’s a collaboration between everyone involved.

How would you say that you make them feel comfortable?

I talk to them. I’ll say, “I’m thinking of doing this—do you like that?” Then I’ll hand them a mirror so they can look at their mouth shape or eye shape. I’ll ask, “Do you want anything else? Do you feel like you need anything before going out on set or doing what you have to do?” I really think models are incredibly brave and generous. They give so much of themselves in a way that few other professions require. No matter how they feel, they’re expected to perform and look perfect on cue. That’s a lot of pressure.

Was there a specific image or anything that sparked something in you that made this path feel inevitable?

That whole era was so inspiring. In the ’70s and ’80s, we watched The Cher Show every weekend. That alone, what else was I going to do with my life? It was incredible. If you look back at it now, you think, “What the hell?” Bob Mackie’s costumes, Cher transforming constantly, it was wild. The same thing with The Carol Burnett Show and I Love Lucy. These women would become entirely different characters through hair, makeup, and wardrobe. That really excited me. I also loved Bette Davis. I remember watching Now, Voyager as a kid, where she transforms from a miserable, frumpy, psychologically damaged woman into this beautiful swan—who’s still emotionally struggling. That stuck with me. It wasn’t the typical narrative of “You’re beautiful now, so everything’s perfect.” She still wasn’t okay, but she looked amazing. She held it together on the outside, even if she was still working through things internally. That idea really inspired me: no matter what we’re going through, we can still make an effort to emerge looking like something special. A look or a style can help you come out of your shell. Of course, it doesn’t fix everything, we all have things we’re dealing with—but style gives you a way to face the world differently. It doesn’t have to be expensive or superficial. If it reflects something real inside you, then it becomes meaningful. Then there were Avedon’s covers, and that Dynasty-era approach to beauty, people really went for it. The celebrities and pop stars back then were older; they were women, and they looked like women. Diana Ross looked like Diana Ross, Barbra Streisand looked like Barbra Streisand, and Dolly Parton looked like Dolly Parton. Everyone had their own thing. It wasn’t this homogenous beauty ideal like we see today. Even for me, I sometimes feel pressured to “pile it on” because it’s my job, and I’m being paid to deliver a look, but working with Miley (Cyrus), which we’ll get to later, has reminded me that you don’t always have to do a lot. Something minimal, something that even looks like a mistake, can be beautiful. I love it when makeup isn’t perfect. Sometimes, when it’s too perfect, it doesn’t let the viewer in. My mom was great at that, she would just rub things on and always look amazing. When I tried doing her makeup like Kevyn Aucoin—tight eyeliner, full face—it didn’t look as good. It lost that charm. Sometimes, her mascara would fall under her eyes, and it just looked cooler that way.

“No matter what we’re going through, we can still make an effort to emerge looking like something special.”

In what ways did studying at Parsons shape your creative lens, especially in how you approach beauty today?

Parsons was great for me—first, because it brought me to New York, and second because I discovered clubbing. I started doing everyone’s hair and makeup in the dorms. It was peak Duran Duran, full ’80s androgynous makeup. At Parsons, I studied painting and graphic design, which were totally new to me, especially typography. I also met Isabel Toledo, and she asked me to do her show. From there, I started working with incredible people early on. I also took photography seriously. I’d already begun shooting in high school, and at Parsons, I basically lived in the darkroom. The most important moment came through a fashion symposium my photography teacher organized. I met Bethann Hardison, Steven Meisel, and Helmut Newton. That changed everything. Bethann was a total game-changer; she told me, “Call me if you need anything,” and I did. I’d go to her agency, and she taught me so much about pushing boundaries creatively and about the importance of diversity. Growing up in Grosse Pointe, I was already sensitive to those dynamics, but she gave language and urgency to things I’d just passively accepted. She made me realize that I didn’t have to accept them and that I should challenge them. Steven Meisel literally told me on the spot that I should be working. I said, “How do you know I’m any good?” and he said, “I can see it on your face,” which of course, was covered in full Duran Duran makeup. I didn’t fully believe him at the time, but he kept showing up for me. I’d bump into him at clubs or sneak into fashion shows, and even in professional settings, he’d always make time. He’d ask how I was doing, answer questions, and just listen. That made me feel so seen, and I’ve never forgotten that. It taught me the value of giving younger people your attention. Sometimes that’s all it takes. Helmut Newton gave a talk at the New School, and I helped him sell books afterward. He was so funny and generous; he signed one of his books and gave it to me as a gift. Years later, we worked together at Vogue, and I reminded him of that moment. He was just as spontaneous and sharp. Watching him adapt creatively in real time taught me so much about flexibility and trusting your instincts. Those three people completely altered the course of my life. I don’t know if I would’ve pursued makeup without them. I never thought this would be my career, but when Steven Meisel says you’re good, you think, “Okay, maybe I won’t be a waiter after all.”

Naomi Campbell and Lindsay Lohan for Visionaire | Image courtesy of The Wall Group

Many people think of you primarily as a makeup artist, but your work spans so much more. You co-founded Visionaire at a time when fashion publishing was undergoing massive shifts. What was the energy like in those early days, and what were you trying to disrupt or create that wasn’t yet in the industry?

It’s hard to remember exactly how things were before the internet and before the explosion of independent magazines. I think the three of us— Cecilia Dean, Stephen Gan, and I, were rebels. I was so turned off by the corporate takeover of fashion and magazines, which we were seeing over and over again. I wanted to be disruptive, as you said in your question. I felt a strong urge to protect and promote creativity, which was always front and center for me. While I was at Parsons and starting to work as a makeup artist, I noticed this commercial mindset that women had to be seen in a very specific way, and I vehemently disagreed with that. At the time, Maison Margiela and Helmut Lang were just beginning to shift the fashion mentality away from that polished, uptown ’80s aesthetic; fashion was supposed to look a certain way, to feel a certain way. That’s hard to imagine now, given how much alternative fashion exists, but back then, it was very rigid. All our friends had incredible personal work, especially the photographers I collaborated with, but there was nowhere to show it. Alternative magazines weren’t really a thing yet, and galleries weren’t showing that kind of photography unless you were someone like Richard Avedon. After a shoot, someone would pull open a drawer and show me a series they’d been working on. I’d be blown away, asking, “What are you going to do with this?” And the answer was always, “I don’t know.” These beautiful projects existed, but they had no home. That’s really what I wanted to change. Of course, there were amazing European magazines like The Face, i-D, or the oversized Manipulator, and we’d all wait anxiously for them to show up at the one newsstand that carried them, but we wanted to create something that felt like a keepsake. Something you wouldn’t throw away. A place for personal work to live and be honored. In many ways, it was what Instagram was in its early days.Visionaire became this experimental space where artists felt safe trying something new, knowing it would be beautifully printed, surrounded by great work, and treated with care. We always mixed generations, young students, emerging artists, and established names like Meisel and Bruce Weber because we wanted it to reflect both what was now and what was next. We just wanted to make something beautiful and lasting.

You created an amazing marketplace for so many creatives to come together, brainstorm, and experiment, which wasn’t done at the time. How did you meet Steven and Cecilia?

I met Steven while we were both at Parsons. He studied photography and took really beautiful pictures. We started doing model test shoots together, and one of the models we worked with was Cecilia Dean. The three of us immediately clicked and became close friends. We traveled to Egypt, went out to clubs, dressed up, and were always surrounded by a really creative circle of friends. Eventually, we all ended up in Paris; Cecilia went to work, I went to study, and Steven started his career there too. We kept that same creative energy going, both in Paris and back in New York. There was a real synergy between the three of us, and our individual talents naturally came together in a way that led to starting this new kind of publication. We didn’t entirely know what we were doing at first, but we had a lot of drive and a strong desire to create something radical. When we started V, I really wanted to fight for artists who didn’t have huge budgets or advertising power. I’ve always been sensitive to bullying, and unfortunately, I’ve seen a lot of it, especially on set. Models get bullied all the time, and I hate it. You don’t get the best work from someone who doesn’t feel safe, seen, or supported. You have to build people up and make them feel like the queen of the night—then they’ll shine and truly express something. Watching a great model is like watching performance art. I mean, look at Shalom Harlow, that’s a performance. It’s incredible. Most people can’t even walk properly down the street, let alone command a runway in front of a thousand people.

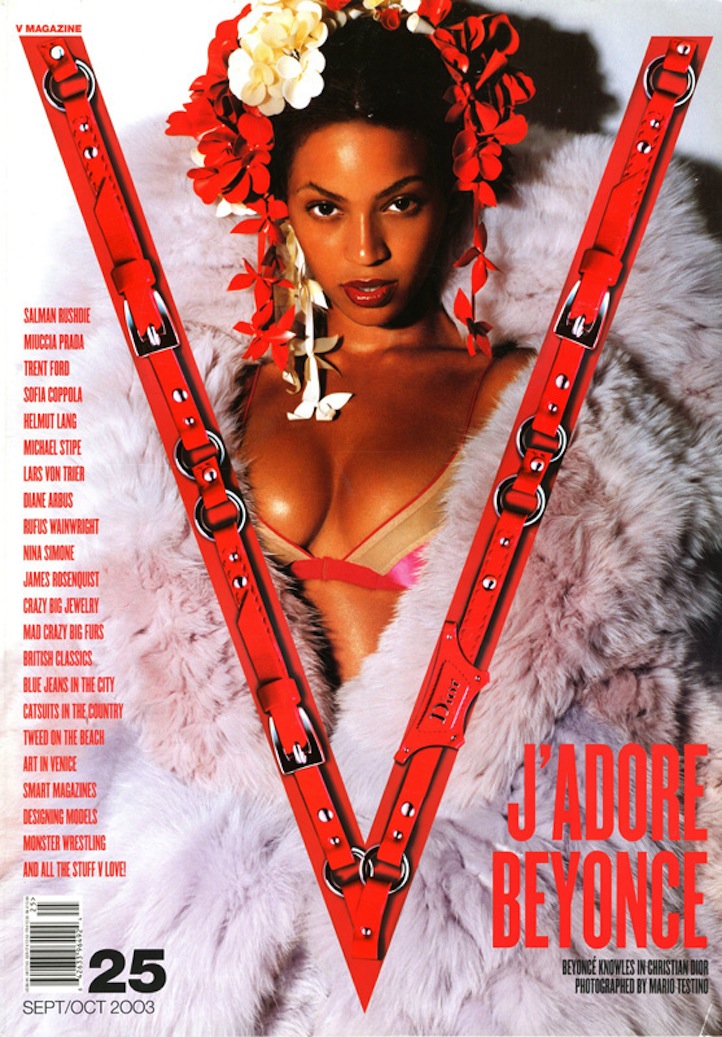

Beyoncé by Mario Testino | Image courtesy of The Wall Group

Not only did you co-found Visionaire, but also V Magazine. How did that foundation in art and publishing shape your perspective, and how does it continue to influence the way you approach beauty and image-making today?

V was an interesting experience. I don’t work with V anymore; I now focus only on Visionaire, but we started V because many of our contributors wanted to shoot fashion editorials. Since Visionaire is thematic, we’d often ask them to explore other ideas, but with so many incredible creatives eager to do fashion stories, we thought, “Let’s create a fashion magazine.” We launched V, but it quickly became more commercial than we expected. I assumed advertisers would understand that, like Visionaire, this would still be a creative project, but they didn’t. They tried to control the editorial, and I found that incredibly frustrating. We were offering them the best photographers and celebrities, but it still wasn’t enough. They treated us like they owned the content, and I pushed back against that. Creativity is taken for granted, and I always want the artist to win. Art feeds all we do, even if people are not aware of it. Still, we had some amazing moments. I remember being on set with Nicole Kidman and asking if she’d wear just a Chanel apron, and she agreed. We put Beyoncé on the cover when she’d just gone solo and wasn’t getting much support. I’ll never forget being on set with Mario Testino when “Crazy in Love” played on a boombox, it was her first time hearing it on the radio. We also gave Lady Gaga her first cover. There was so much diversity, and we often featured people simply because we admired them, not because they had something to promote. The best part was working with photographers and stylists who truly got it, who saw V as a chance to be bold in ways they couldn’t with more traditional magazines. V stood for independent thinking. It gave artists room to experiment, which I think is essential. If all you do is shoot for magazines with narrow parameters, you lose creative range. Visionaire and V offered that freedom. The office itself reflected that spirit, open, no hierarchy. Editors, interns, and everyone worked side by side. Sure, it lacked privacy, but it fostered collaboration, and I’m proud that so many people who passed through V and Visionaire are now spread throughout the industry in fashion houses, magazines, and agencies. There’s a quiet legacy there, a ripple of creativity that still moves through the industry.

“Creativity is taken for granted, and I always want the artist to win. Art feeds all we do, even if people are not aware of it.”

It feels like autonomy is really important to you.

Absolutely. Personal creativity is essential; it’s healing. Everyone has psychological challenges or life issues, and I believe the creative process can be an evolutionary act that helps us move through them. It pulls us out of limiting ways of thinking. Conservatism, for example, tends to be restrictive, while creativity is expansive. Art, fashion, photography, video, they all help break those boundaries. It’s not just about imagining something; it’s about manifesting it visually and physically. That act frees ideas from being stuck in your head. I recently saw a post by Douglas Keeve about Supreme Models, with a carousel of incredible Black women in fashion. Iman said, “There’s nothing like a Black model on the runway.” And it hit me—Black models didn’t just participate in fashion; they transformed it. I grew up during a time when they were already a force, so I hadn’t really considered what it looked like before. But their presence changed everything: how we see movement, beauty, and expression. Their impact on fashion, music videos, and culture created a seismic shift that we’re still drawing from; even if we don’t always realize it.

What did working with creatives like Steven Meisel, Karl Lagerfeld, and Steven Klein, teach you about image-making? Do you recall a specific shoot where the collaboration changed how you thought about beauty or storytelling?

I started with Steven Klein; he was the first to book me consistently when I was really young. He had gone to RISD, and everyone I know from there has such a specific, remarkable approach to art. Steven wouldn’t take a picture unless he was completely inspired by everything happening on set. We’d change the model’s clothes, hair, and makeup over and over again. He’d try different lighting setups and camera settings; his technical mastery was incredible. We’d work until four in the morning, come back the next day, and sometimes scrap everything to start fresh. It taught me not to hold on too tightly. I’d think, “That was the best purple lip I’ve ever done,” and he’d just say, “Wipe it off.” That practice of constant reinvention was invaluable, even if it drove us all a little crazy. Working with Karl Lagerfeld was another formative experience. He was brilliant, hilarious, and endlessly witty, people don’t realize how funny he was. We’d shoot Chanel catalogs just a week before the shows, often working until 5 a.m. He’d reference obscure silent films or quote Mae West, and somehow, we just clicked on those things. He was never rigid, and always open to experimentation and creative flow. He really valued spontaneity. Then came my first shoot with Steven Meisel for Italian Vogue, a military-themed story. It was my big moment, working with the person who had supported me from the beginning. He told me we’d work everything out on set, so we prepped the models lightly. But once I saw them standing there, fully dressed under the lights, I knew I couldn’t just do “no-makeup makeup” for Steven Meisel. I grabbed my cream eyeshadows, dug in with my fingers, and started swiping bold colors directly onto each model’s face. Each look was improvised on the spot. The story ended up running in black and white, but that moment was so freeing that it felt like I had finally stepped into my full creative power in front of someone I deeply respected. It was full circle: from student to collaborator. That shoot marked a turning point, and we worked together for a while after that. Now, when I’m leading a team at a show, I try to bring that same supportive energy—never mean, always encouraging. I’m not saying I’m perfect, but I’ve tried to be really kind and supportive all the time because I feel like you get the best work out of people. I mean, at least for me, I need to feel supported and seen and safe. If someone’s on my shoulder, I’m not going to do a great job.

Visionaire 18th fashion special | Image courtesy of The Wall Group

What makes a good collaboration for you?

One of our best collaborations at Visionaire was for our 18th fashion special, which came in a Louis Vuitton envelope. For that issue, we paired creatives together Nan Goldin came by the office one day, and we asked her to shoot a fashion story—something she hadn’t really done before. She said, “I really like Helmut Lang.” So we called Helmut and said, “Nan wants to do something with you,” and he immediately said, “Amazing, I love Nan.” They teamed up, and what came out of it was this incredible set of images. People were blown away. It was at the peak of heroin chic—very raw, very real, and unapologetically of the moment. Nan, James King, and Helmut’s designs all just aligned. That shoot really changed things in fashion. After that, everyone started chasing fashion-art collaborations. To answer your question, I think the best collaborations happen when there’s mutual admiration and respect. It’s about both people showing up as themselves and bringing their full creative voice. Miley (Cyrus) once told me something Dolly Parton said to her: “You do you, and I’ll do me—and together, we’ll be us.” That’s it.A great collaboration isn’t about blending into one another—it’s about two strong individuals creating something new together. That’s when the magic happens.”

You’ve worked with beauty brands like MAC Cosmetics, Fenty Beauty, Tom Ford Beauty, and Nars Cosmetics. What makes a beauty brand partnership meaningful to you? Is it innovation, artistry, or something more personal?

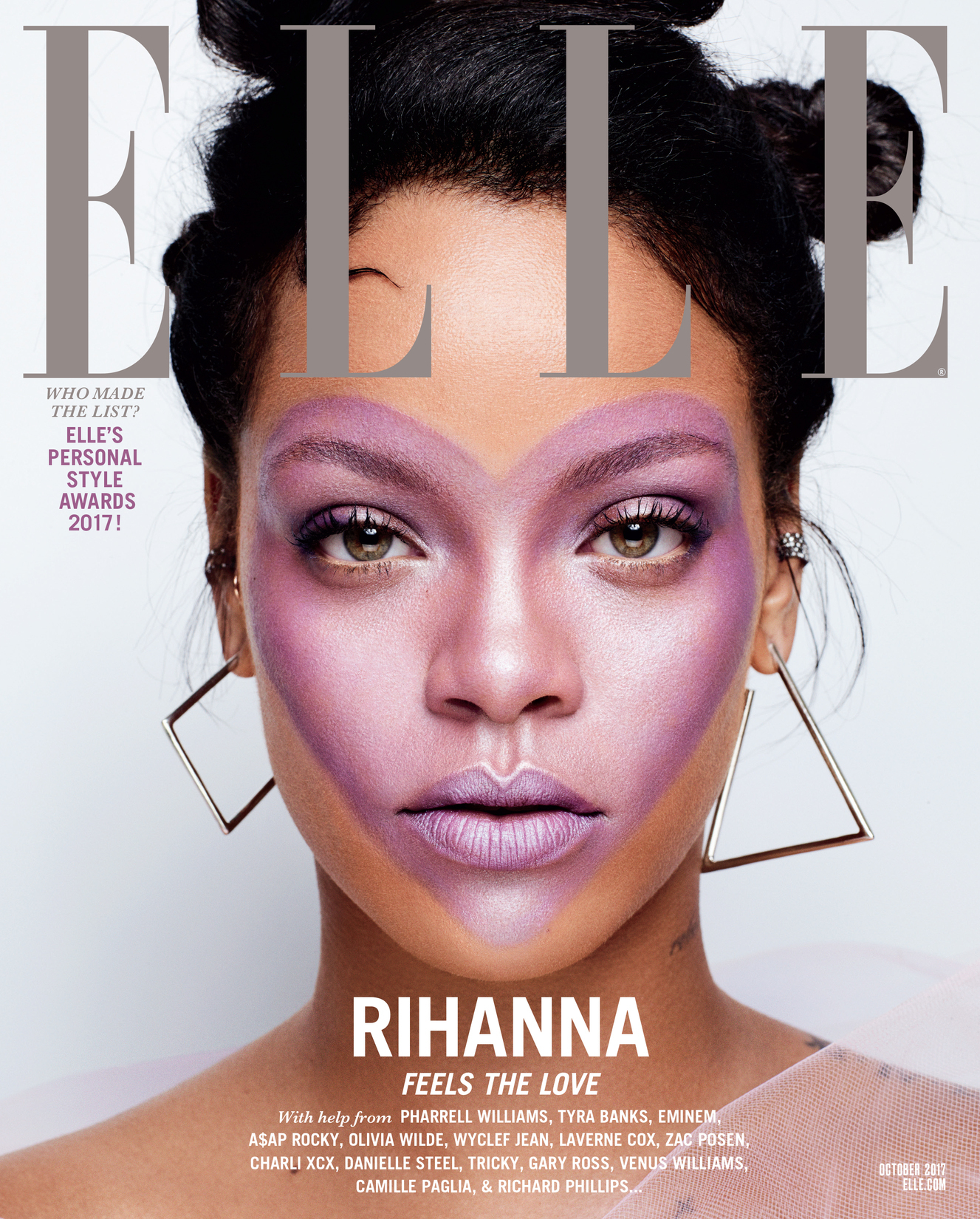

What I love most is digging into what a brand truly represents. That absolutely affects how I approach things. Maybe it’s because of Visionaire, but I tend to think thematically. When I work with Shiseido, for example, I immediately think of Serge Lutens. With Tom Ford Beauty, I imagine the world he’s built, and I kind of step into character, almost like an actor. It’s not just about creating a look for the model; it’s also about me entering the creative mindset of that brand. I loved working with Francois Nars. He has impeccable taste—rooted in 1970s French Vogue—but he’s also unafraid to push boundaries and embrace strange, unexpected beauty. That kind of open-minded creativity is so inspiring. With Fenty Beauty, Rihanna brings this spontaneous, razor-sharp vision. She makes split-second creative decisions that are always right. It’s amazing to watch and to rise to that challenge. Each brand has its own world, its own version of beauty, and I have to adapt. Whether it’s Maybelline or Fenty, I step into their lens of how women should feel and be seen. Now that I’m creative directing for some brands, I love working on everything, from typography and packaging to sustainability and casting. You start to realize how much goes into a single product, things you take for granted when you just pick it up. I try to stay personal in my approach. Even when a marketing director tells me what a product should represent, I focus on the person in front of me, their skin, their energy, and their beauty, and use the products to bring that out. That’s what keeps it meaningful.

Rihanna by Sølve Sundsbø | Image courtesy of The Wall Group

You’ve been collaborating with Miley Cyrus for over a decade now, most recently appearing in her “Easy Lover” video from her “Something Beautiful” album. How would you describe the evolution of her beauty aesthetic—and your creative relationship?

I made the cut! We met at the Visionaire offices days before her V cover shoot with Oribe and Carlyne Cerf De Dudzeele. We locked eyes, and that was it—I was hooked forever. I love Miley. She has this incredible mix of raw human qualities, immense talent, and that voice. I get to hear her warming up, inches from my face, as I do her makeup. I love her face, and she has a great sense of fashion and beauty, so I have always encouraged her to be true to herself and to what she feels in the moment, and my goal is just to enhance that on camera. She’s constantly evolving, shaped by her new work, and I move with her—and her genius team. We started with almost no makeup, really minimal, even for covers, TV, and events. We didn’t let the pressure push us into doing more. Now we’ve found this rhythm of in-the-moment creativity, experimenting when the mood strikes. Something Beautiful was an epic project, and I can’t wait for it to be released. There are definitely a few looks in there to unpack. It actually reminded me of my early days shooting with Steven Klein, just totally in the moment. Miley’s great at knowing when we’ve got it, and sometimes, we’d wrap early and squeeze in an extra video. One day, we were in this tiny, forgotten room off a cavernous Paramount set, steaming a giant Mugler look, fixing lashes, redoing hair—it was chaos, but we pulled it off. The crew would create entire sets on the fly, and we’d just make it happen. It was unplanned, spontaneous, and so exciting. I really can’t wait for people to see it. We need alternate women out there who are not just doing that one thing. I have full respect for her and her creativity.

Miley Cyrus by Alasdair McLellan | Image courtesy of The Wall Group

Looking back on your multi-hyphenate career as an art director, editor, makeup artist, and more, what advice would you give to creatives today who want to resist being boxed into one lane?

I’d say: learn your craft and then really learn the history behind it. Know it inside and out. Develop your style, not just in your work, but in how you move through the world. Style isn’t only about lighting in a photo, it’s how you behave on set, how you treat people, the words you use, how you dress, and how you carry yourself. Move with grace. Be aware of the power you have to create change. Every creative act matters. Your words and thoughts have power, so stay positive and intentional with them. I’ve noticed a shift in younger people. Everyone’s like, “I’m an art director,” or “I’m a photographer.” I once asked someone what camera they used, and she said, “I don’t have one.” I was like, “Do you take pictures with your mind?” You have to actually do the work. I love dancing, but I wouldn’t call myself a dancer—unless I committed to it. You have to put in the time. Work on your craft, know it, and it’ll give you confidence. The more you learn about it, the more you can really own it yourself, and you won’t feel like an imposter. Definitely explore whatever interests you and go towards your interests. Do something you like to do because no matter what you do, you’re going to spend hours doing it.

James Kaliardos | Image courtesy of The Wall Group