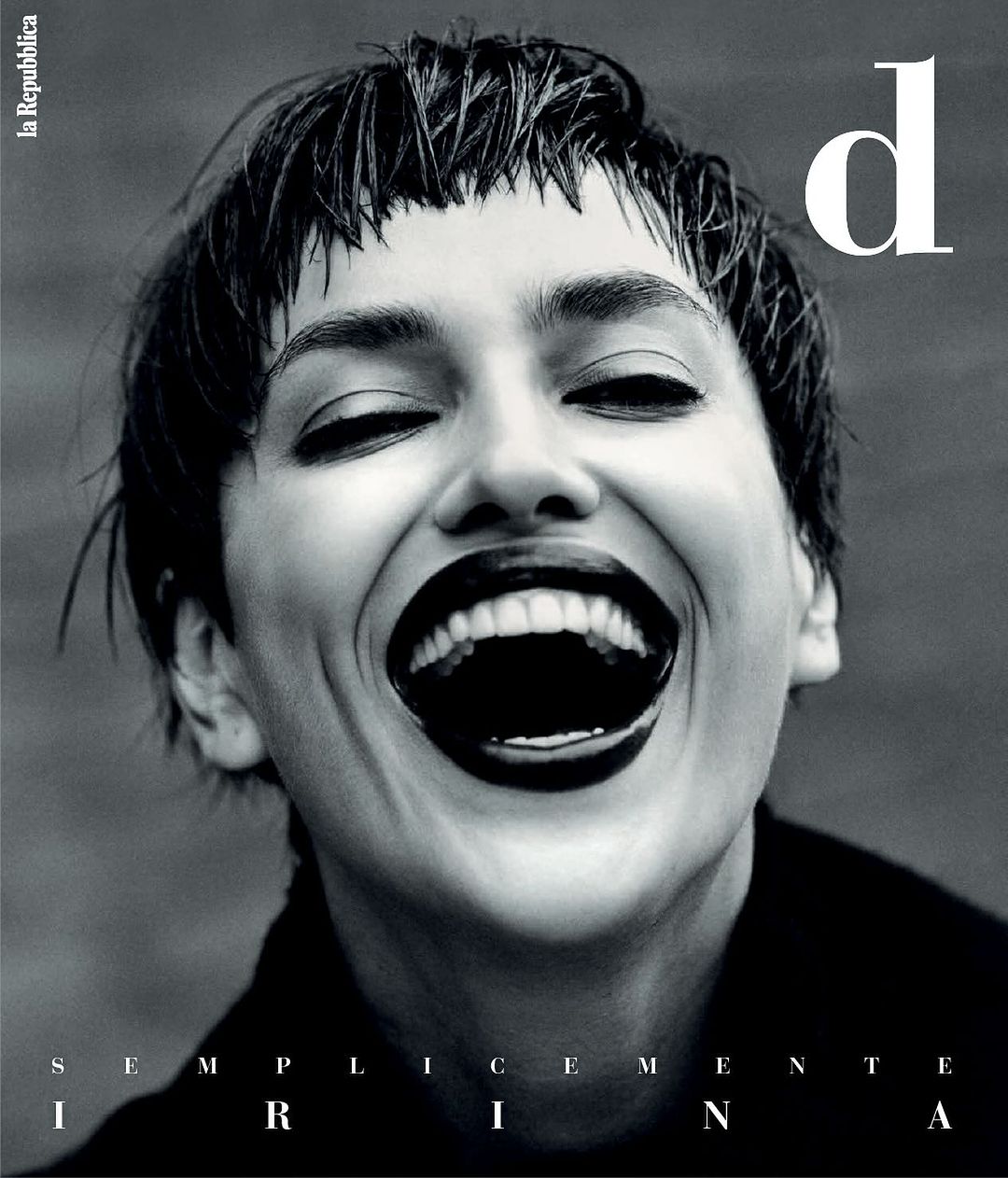

Irina Shayk by Luis Alberto Rodriguez | Image courtesy of MA + Group

British makeup artist Dick Page helped define what we now call the “no makeup makeup” look at a time when fashion was dominated by polished glamour. His eye for beauty was shaped early, growing up in England and discovering the fantasy of performance at the Bristol Old Vic. That theatrical sense of storytelling carried into his work in the late ’80s and early ’90s, when collaborations with stylist Melanie Ward and photographer Corinne Day on Kate Moss editorials for The Face Magazine and i-D Magazine caught Calvin Klein’s attention. Soon after, Page was in New York, keying the designer’s runway shows and campaigns for nearly a decade. Page’s philosophy has always been clear, “The goal is not to correct someone into a mold but to accentuate what makes them compelling.” That approach has fueled an almost 30-year creative partnership with Michael Kors, as well as recent projects like Julian Klausner’s debut at Dries Van Noten and campaigns for Saint Laurent and Chanel. Along the way, he has worked with some of the industry’s most defining image-makers, including Inez and Vinoodh, Juergen Teller, and Camilla Nickerson. Ahead of leading Michael Kors’ Spring/Summer 2026 show beauty looks, which opened New York Fashion Week, Models.com spoke with the industry veteran about his beauty idols, the power of collaboration, and why individuality over perfection remains his guiding principle.

Liu Wen and Binx Walton by Gray Sorrenti | Image courtesy of MA + Group

I read that you were a theatre kid. Where did you grow up, and what was your relationship to beauty like then?

I was born on the south coast of England and grew up in the southwest. Thinking about your question, I had not considered its timeline before, but theatre felt like a natural extension of play. We grow up playing, making things up, and carrying on with our imaginations. For most people, that gets knocked out of you when you become an adult. You have to do adult things, and you do not get to play anymore unless you are an actor or a performer of some kind. For me, watching the fantasia of people on stage felt like an extension of that play. I was lucky to grow up in a place with incredible theatre. The Bristol Old Vic Theatre School and the Bristol Old Vic Theatre were only about eight or nine miles from where I lived, and almost everyone you can think of in British film and theatre trained there. It was an extraordinary environment to be exposed to. I was fortunate to see those productions, to read plays in school, and to study English literature and language. Reading those works and then watching them performed created this magical suspension of disbelief. You know it is not real, but for that moment, you allow yourself to believe, which connects closely to fashion. One of my favorite memories that ties theatre and fashion together came from a conversation with my mum. I had sent her a magazine I worked on, and I was excited for her to see it. She looked at it and asked, “Why does she keep changing her clothes? Who is she, and why does she keep changing?” I had never thought about it that way, but she was right. It is strange when you consider it literally. That moment reminded me that the play-acting, the fantasia, and the performance of fashion are, in many ways, all theatre.

You didn’t assist but cold-called magazines, which eventually led to work with publications like The Face Magazine and i-D Magazine. Do you remember your very first job? What was going through your mind at the time?

My very first job was most likely for one of those free magazines they used to hand out at tube stations in London around 1987. There was Miss London and Girl About Town. They were mostly filled with ads and had a few fairly mediocre fashion shoots. Everyone from my peer group, people around my age or a few years either side, worked on those magazines at some point. The covers of Miss London and Girl About Town were poppy, light fashion images, sometimes with a slightly edgy twist. These magazines were not even sold on stands. They were simply handed out as you came out of the train in the morning, when you were probably at your worst, crawling up from the underground, and someone would hand you one, saying, “Here, have a magazine.” My first job was one of those, and of course, because I had never worked on anything at that scale before, I was really excited. To have a magazine I could show someone and say, “This is my work, this is a real job,” felt huge. It was proof I was doing something real.

Do you remember how you got that job?

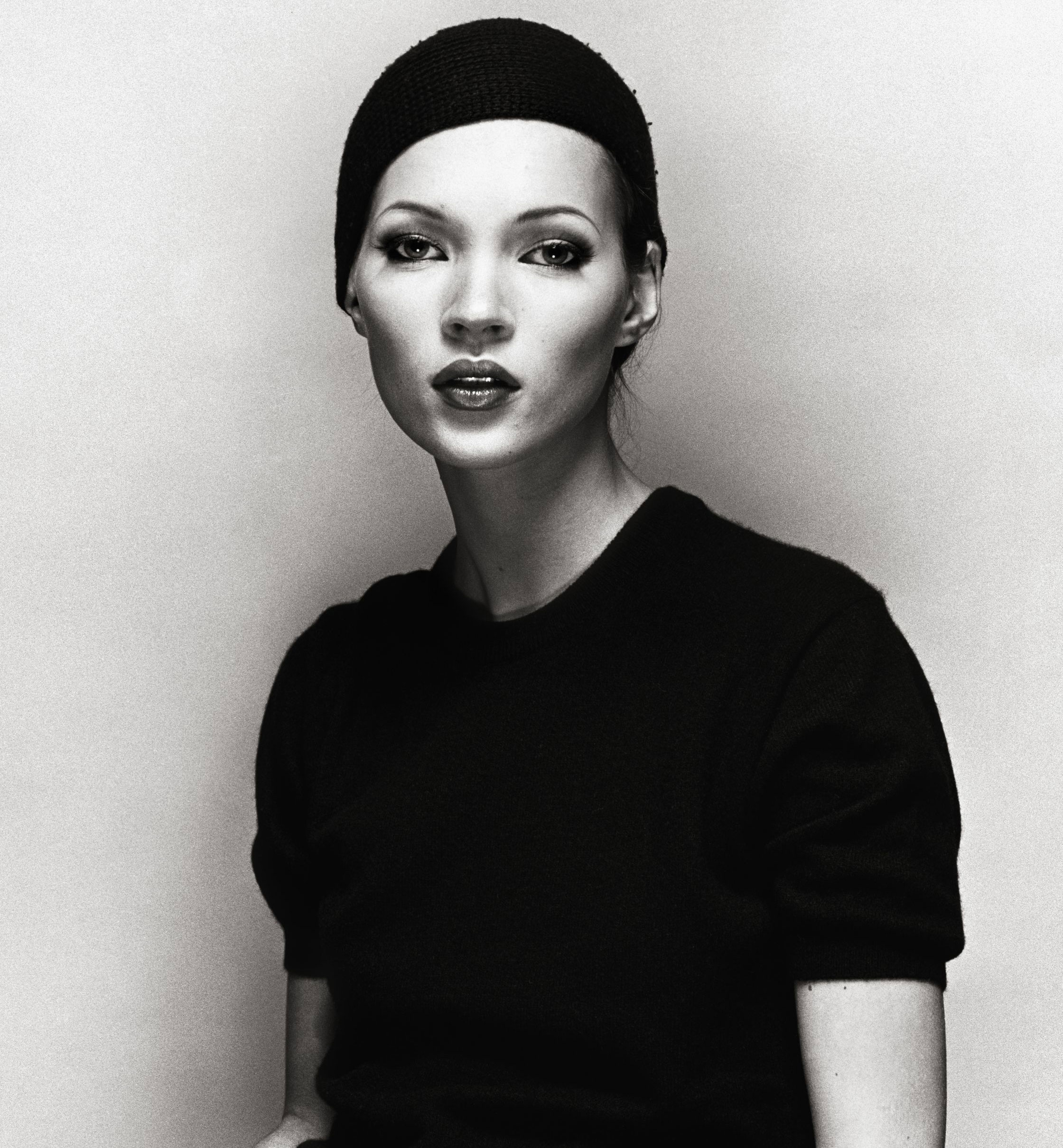

I had an agent. I moved to London in 1987 and started knocking around, trying to meet people. A lot of them said no, because I was coming from Bristol with only local newspaper and magazine tear sheets. The southwest of England was not such a big city then. This was all before social media exploded, when you could now live and work in fashion almost anywhere in the world. I saw a bunch of agencies, and most of them had no interest in me. Zed Agency eventually took me on. Zed mostly represented kooky models who did really well in Japan, or indie types who worked with The Face Magazine, i-D Magazine, and BLITZ Magazine. Through them, I started going on go-sees and meeting people, you could call people up, but mostly it was word of mouth. The Face and i-D came about through Melanie Ward, she is still one of the most influential stylists in fashion. We met in 1987, and she connected me with Corinne Day, then with David Sims. I met Juergen Teller on my own, as well as Nigel Shafran and Donald Christie, some of the key English photographers at that time. My first job for The Face Magazine came in 1989 with Kate Moss. In between, I kept part-time jobs to put food on the table. The Face and i-D had been around a while, but felt new and exciting to me. They were not mainstream like Elle or Vogue. Those magazines would not have touched me with a ten-foot pole until I came to America. Then suddenly they were interested, saying, “Oh, wait, we’d like to book him now.” It was very much after the fact.

Your work caught Calvin Klein’s attention, which led to your first major runway show in 1993. What was that experience like, and how did you prepare for it?

Polly Hamilton was styling at Calvin Klein at the time, and Kate Moss had just signed with the brand the year before. Many of us, including Guido Palau, Melanie Ward, and others, had worked closely with Kate from the beginning, so there was already a shared circle of people. Fabien Baron was involved with Calvin, and Liz Tilberis was relaunching Harper’s Bazaar U.S., with Fabien designing it. Those connections in New York opened the door for me and Guido. They called my agent and asked if I liked doing fashion shows. She said yes, even though I had not done one at that level before, and there was no easy way to check at the time. I flew to New York, met with Calvin and Polly, and did a quick test. Calvin asked, “That’s it?” and I said, “Yes.” That was the beginning of nearly a decade of doing the Calvin shows, advertising, and a lot of Bazaar work. I moved to New York around 1993–94, first subletting, then settling into my own place by 1994 as the work kept coming.

Kate Moss by Glen Luchford | Image courtesy of MA + Group

You came to New York for Calvin Klein?

Yes, for Calvin Klein and Harper’s Bazaar U.S. Those projects happened within a few months of each other, and they kept me in New York. Once I landed, everything moved quickly. I was being booked for all kinds of work. At that time, it was easier to arrive as a new face because people did not have instant access to every corner of the fashion world the way they do now with social media. You had to hunt down British magazines in America or American ones in England, which meant there was still room to feel new and surprising. I remember the assistants at my first Calvin show asking, “Who is this? Where did she come from?” because I had never had assistants before. One story that stands out is when I went to buy lipstick for the show. I asked for six tubes of a shade called Aubergine from Il Makiage at Bendels. The saleswoman asked if I was working on the shows and then assumed I was assisting François. When I explained I was doing Calvin’s show myself, she patted my hand and said, “No, honey, Francois Nars does Calvin.”

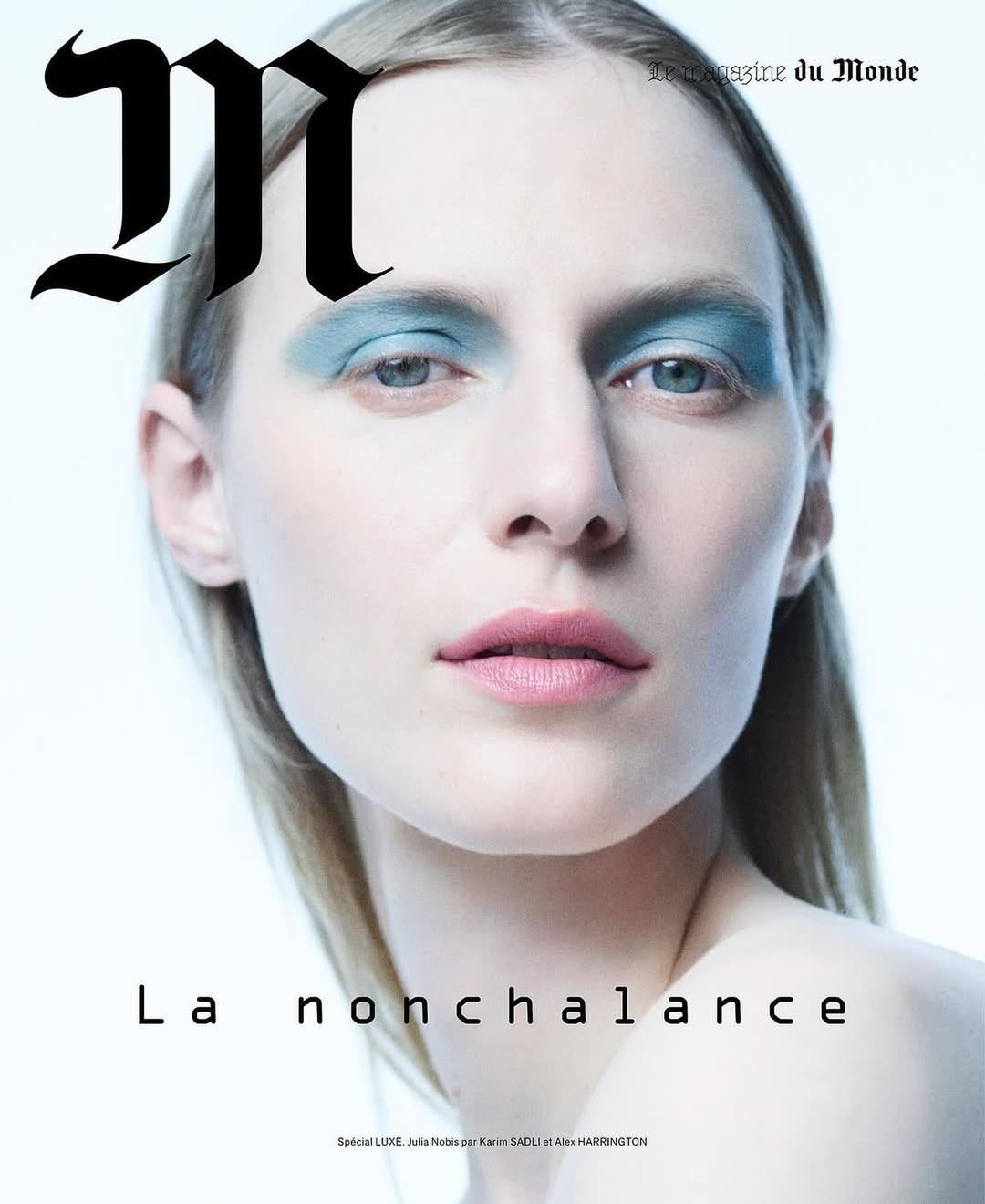

Julia Nobis by Karim Sadli | Image courtesy of MA + Group

Who were your beauty idols growing up, and what was it about them that resonated with you?

For me, beauty has always been about the person and their signature, something singular that makes them unforgettable. I love the idea of someone who finds their look and carries it for a lifetime, like a grandmother who puts on red lipstick at 15 and wears it until 90. I was drawn to performers who animated their faces and bodies. Actresses like Glenda Jackson fascinated me with her presence, voice, and projection. In the 1970s, I admired glamorous British TV presenters, especially Patti Boulaye, who was so elegant and goddess-like on screen. Music also shaped my idea of beauty. I loved the DIY aesthetic of punk, where you could invent your look as you went along. Debbie Harry was strikingly beautiful yet subversive in Blondie’s early years. Siouxsie Sioux brought strangeness and edge, while Polly Styrene radiated energy and force, even if she did not fit conventional beauty standards. Pauline Black of The Selecter embodied strength and style in the two-tone ska movement. Then there were icons like Annie Lennox and Grace Jones, both redefining beauty through androgyny and power. What all of them had in common was that they could not be anyone else. They might perform as different characters, but the essential quality that made them compelling was entirely their own.

“Even with dramatic looks, I want the person to remain visible. I am not interested in disguising or reshaping people to fit a single idea of beauty.”

How would you describe your work? What would you say is your trademark?

I became known for what people called “nothing” makeup. At the time, there were already natural looks: the sporty Bruce Weber aesthetic and the sculpted beige tones of Kevyn Aucoin. What I did was different. It was minimal, like lipstick on the cheeks or nose and Vaseline on the eyes, things I developed with David (Sims), Melanie (Ward), and Corinne (Day). That raw, bare approach became tied to grunge in North America but actually came out of English street culture and magazines like The Face in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Even with dramatic looks, I want the person to remain visible. I am not interested in disguising or reshaping people to fit a single idea of beauty. I remember the writer Lucy Grealy said, “the most popular girls at school were the ones best at looking like everyone else.” That normalization to me is one of the worst things to happen in beauty. Everyone chasing a single ideal means there will always be someone taller, blonder, or closer to that standard than you. My approach is to help people create their own version of beauty, whether dramatic, understated, or simply a clean face and sunscreen. I used to think sameness was just a drift in beauty, but now it feels like a stampede driven by trends. To me, the goal is not to correct someone into a mold but to accentuate what makes them compelling. Models are in my chair because they already look great. My role is to enhance that, not erase it.

Mona Tougaard by Inez and Vinoodh | Image courtesy of MA + Group

You’ve collaborated with Michael Kors Collection since 1996. What does your creative process look like when working with him season after season?

Working with Michael (Kors) is always light, even during the stress of fashion week. He has a great sense of narrative and often frames each season around a story. He might say, “She’s been in Capri, now she’s off to Aspen,” or describe how the woman he envisions throws her hair up or steps off a boat for dinner. His references give us a character to build from. Michael also recognizes the individuality of beauty. He never wants to make everyone look the same. He likes a dry eyebrow, subtle bloom in the skin, and makeup that enhances natural coloring rather than changing it. Blondes might get a soft taupe-gray brow, while others keep the natural texture of their skin with just a touch of health and color. The goal is to keep each model believable and specific to herself while still existing within Michael’s world. From there, Orlando (Pita) and I test looks on a handful of models and adjust with input from Michael, his husband Lance, and Carlos (Nazario). We fine-tune details: how hair interacts with clothing, how lighting and venue affect makeup, or how live music might shift the atmosphere. Like any runway test, it is a balance of small tweaks, but Michael’s particular talent lies in creating a complete environment. The show becomes a world, presenting a clear vision of this woman for that moment on the runway, even if most people will later experience it through photos or social media.

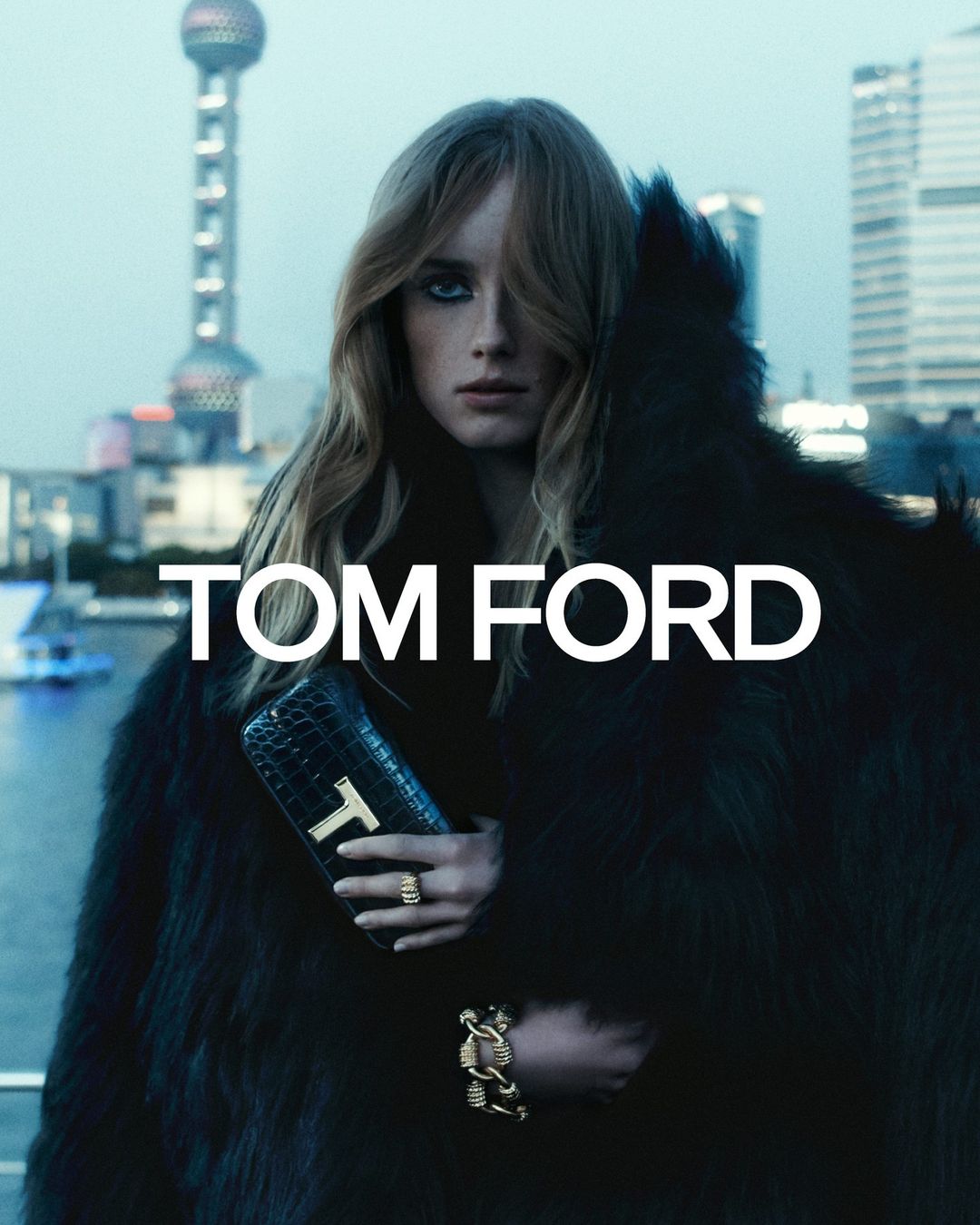

How would you say that differs from campaigns?

In campaigns, the focus can be very specific. Sometimes it is all about the shoe or the bag, regardless of what else the model is wearing. In fashion campaigns, it varies. Some feel lifestyle-oriented and loose, with clothes and accessories shown more casually. Other times, there is a very strict mood board referencing a photographer’s past work, a film still, or another inspiration. For years, I worked on Marc Jacobs campaigns with Juergen Teller. Marc often had ideas about who he wanted to photograph, and we would just make it happen. Those shoots were some of the most hands-off I have experienced for a major fashion house. Peter Miles did the art direction, and Marc trusted everyone to create the world without over-controlling the process. Marc approached the shows similarly, he always had a strong vision, but still encouraged us to play and bring our own ideas. I have been lucky to work with people like Helmut Lang and Melanie Ward, who trusted me to contribute and understood that not every idea would make it to the runway. Campaigns and shows also depend heavily on resources, sometimes you have a multimillion-dollar production and other times, you have one model for one hour in a cramped studio, and you have to make it work. I enjoy both ends of that spectrum, the DIY spirit is where I started, and I still value that energy just as much as large-scale productions.

What’s the craziest impromptu situation you’ve had to navigate on a job, and how did you handle it?

There have been many since this work changes daily, and there are always moving parts. Things can go wrong more easily than in a regular job, but thankfully, real accidents are rare. One of the most dramatic moments happened on a shoot in Italy with Mariacarla Boscono. We were in a palazzo on the Grand Canal, and after getting her hair and makeup ready, we left by boat for the location. As we moved into the sunlight, she suddenly said, “What did you put on my face? It’s really itchy.” Within seconds, her skin broke out in massive red hives. It was a terrifying moment. The producer, Emanuele Mazzoni, immediately got her to a hospital, where she was treated with an epinephrine shot. We later learned it was a photosensitive reaction to shellfish she had eaten the night before, not the products I had used. Once it calmed down, we were able to continue, but in that moment, I thought I might have ended her career. Another memorable situation was during a Loewe show in Paris, when Narciso Rodriguez was designing. Some models arrived straight from another show with large transfer tattoos painted on their bodies, including big skeletons on their backs. We could not remove them, so the team had to paint over them in layers, almost like house paint, since proper tattoo cover products were not common at the time. In the end, a few outfit changes helped solve the issue.

Amelia Gray by Collier Schorr | Image courtesy of MA + Group

You returned to The Face for their Winter 2024 covers. What was it like coming full circle with a magazine that played such a formative role early in your career?

It was funny because on that shoot, most of the team had not even been born when I first worked for The Face. Amelia (Gray) was really committed to inhabiting these characters for Collier (Schorr’s) vision, which made the story strong. I would not have known it was the same magazine, because The Face has gone through so many versions. When it started, it was about Britain’s music, youth, and fashion culture, presented in a more polished way than i-D Magazine, which came directly from street casting. I worked for both, so coming back now felt like returning to the scene but doing something new. That is what made this project exciting. Many places would not allow that level of play, but here we could experiment. It is always a little strange to revisit something you have done before, and you do not want to simply repeat yourself. Of course, the past pops up often—when I look at mood boards for ad jobs, I sometimes recognize 30 percent of the references as work I have done. But to return to The Face and create something fresh instead of retreading the past felt right.

You recently worked with Julian Klausner, Dries Van Noten’s new creative director, and keyed his debut men’s show, a moment of great anticipation for the brand. How did that collaboration begin, and what was your beauty vision for helping shape this new chapter?

I first worked with Julian (Klausner) in January in Antwerp on the F/W 25 men’s lookbook with Willy Vanderperre. What began as a simple hair and makeup test turned into several shoot days, and the process unfolded gradually and naturally. Dries has a strong family atmosphere, with many people who have been there for years, so it was a very collaborative and comfortable environment. They later asked me to do the menswear show in Paris this September. Julian described the characters as if they had been out all night, waking up on the beach, beautiful but a little rough. To capture that, I mixed five different cream colors to create subtle shadows around the eyes, like under-eye bags, which I find very beautiful. I am not a fan of concealer or erasing everything; I prefer skin that looks real, flushed, and a bit raw. I created that look myself on all 60 models in what felt like a conveyor belt backstage during a Paris heat wave. The process was very collaborative. Robbie Spencer, Julian ( Klausner), and Dries’ internal team gave input, while Olivier Schawalder worked on the hair. We tested, adjusted, and refined the look on the models in their clothes until it felt right. The whole experience was generous, fluid, and easy. You do not always click with everyone, but this collaboration had a natural flow that made the work a pleasure.

Having worked in the industry since the ‘80s, what major shifts have you witnessed? Are there particular trends, changes, or moments that stand out to you?

The biggest shift has been the arrival of the computer, the internet, and social media. When I started, none of that existed. Today, everything is instantly accessible, and while that has benefits, it has also changed how we experience fashion. One of the things we have lost is mystery. With constant behind-the-scenes content, it is easy to forget that the magic of fashion should be the reveal when the first model steps onto the runway and sets the tone for the show. That sense of anticipation has been eroded by our obsession with instant gratification and short attention spans. Social media has also disrupted the idea of editorial storytelling. Magazines once curated fashion stories with intention and structure. Now we often see images pulled apart and consumed one by one, which can feel overwhelming. Instead of a narrative, fashion becomes a grab bag of visuals. Still, there are positives. We can research artisans, fabrics, and processes in ways that were never possible before. Progress is not always purely good or bad, it shifts, evolves, and keeps the industry alive. Designers handle it differently; Marc Jacobs, for instance, is happy to make a complete turnaround each season, while others like Narciso Rodriguez or Helmut Lang build on their work more gradually. So, the big advantage we have from the beauty side of things is that we can wash it off. There is no massive commitment. Until you take the needle or the knife to your face, you are safe, the paint is temporary.

Rianne Van Rompaey by Robin Galiegue | Image courtesy of MA + Group

What non-fashion influences, whether art, film, food, literature, or music, inform or inspire your approach to beauty?

Most of my influences are outside fashion. Color has always been central, from Josef Albers’ studies of contrast to a Japanese color dictionary filled with unexpected combinations. I also look to painters like John Singer Sargent, Mark Rothko, Paula Rego, and Alice Neel, as well as performers and musicians who use their faces and bodies with energy and presence. It is less about copying a look and more about capturing a feeling. Film is another constant reference, especially the work of directors like Stanley Kubrick and David Lynch, as well as the cinematographers who shaped their atmosphere. Also, cooking has always been something I enjoy, and it has become a fun social thing. I love seeing how other people cook, discovering new restaurants through social media, and even tracking chefs or places down. Food is a huge part of my life. I cook almost every night when I am home, and even when I travel, I try to cook whenever I can. Above all, I believe in staying open to the world. Inspiration comes from being present, in the subway, on the street, or in everyday encounters, rather than cutting yourself off.

As someone with so much experience, what advice would you give to young makeup artists trying to break into the industry?

First, know your craft. You should be so skilled that the techniques feel automatic, allowing you to focus on the bigger picture. Understand your process, understand how your work fits into the story being told, and always be prepared. Equally important are the basics: show up on time, be kind, be helpful, and never make someone’s day harder. Collaboration is key, makeup is rarely the sole focus; it has to harmonize with the clothes, the hair, the lighting, and the mood. Sometimes your work is celebrated, sometimes it is invisible, but both can mean success if the whole picture works. Check your ego at the door. You are there to contribute to a team, not to dominate it. That requires emotional intelligence, knowing how to read the room, when to push, and when to step back. The job does not exist in a vacuum; it is social, collaborative, and built on trust. Finally, remember that your work is part of something bigger than yourself. Even if your name is on it, you are contributing to the story, the show, or the image. It is better to be a small part of a great picture than a big part of a disaster.

Dick Page | Image courtesy of MA + Group