Behind the Image is an ongoing MODELS.com series taking a more personal look at both established and emerging creative talent.

Szilveszter Mako

Szilveszter Mako, Photographer

Hometown: Miskolc, Hungary

Based: Milan, Italy

How did you first discover your passion for photography, and what specifically led you into the world of fashion photography?

My path to photography wasn’t direct. It was nonlinear and heavily influenced by creative exploration. I moved through many forms of creative expression until I found my balance and clarity in photography. My first impactful photograph traces back to Lillafüred, Hungary, where I grew up. Prompted by a classmate’s suggestion during a prestigious secondary school academic competition, I used photography as my medium. Around this same period, in 2007, when I was 15, I began experimenting with emo hairstyles, photographing each finished look. I’m still very proud of that work. Throughout every creative medium I explored, photography was an ever-present undercurrent. It’s a medium I can control, something not merely important to me but instinctive. There’s a fleetingness to photography. A moment passes in a breath, but in that moment, I have complete creative sovereignty over how it’s held, framed, and remembered. Each element is shaped by my choices. I sit behind the lens as much as I create the image before you. I don’t like to define myself strictly as a photographer; I orchestrate the entire tableau. I craft the image before it ever meets the lens, and I want this to be heard and known. I’m not defining myself solely as a photographer. Photography simply allows me to set boundaries while expressing the freedom of my art within a single image. I can’t pinpoint exactly when or why it happened, but fashion photography seemed to hold my attention more than any other form. I was drawn to people and the stories they tell through clothing, posture, expression, and presence.

How would you describe your work? What’s your trademark?

The foundation of my work is a composed synthesis of natural light and texture. Texture is very important to me, and everything else follows from that. Natural light is my native language, though I can’t deny my work with digital, just as I won’t deny my use of analog. I exist somewhere between the two. The process I use to develop my photographs is kept quiet; I prefer to hold it close. What I will share is that it demands patience, obsession, and a labored hand. I also have an idealistic view of how I portray my images; nothing in my photographs is purely realistic. When I’m retouching, I approach it with a sense of ancient Greek idealization. I’m conservative in taste. I don’t care for overt sexiness, excessive heels, or forced posturing. I grew up under conservative restrictions and rules, and those influences have never entirely left me. I struggle with them, but they also shape who I am and the art I create. I owe the very core of who I am to my grandparents. I grew up surrounded by the discipline and resilience of the elder generation of Eastern European Soviets, values deeply instilled in me. Yes, they were strict and extremely conservative, but I am grateful to have been raised by them. What I lived among was a routine rhythm of labor and factories, built upon coal, dust, and bare brick walls. My grandparents have witnessed history being made.

Your work has a Renaissance quality, often evoking the texture of drawings or paintings. What draws you to this period, and how does it shape your creative process?

Undeniably, there are overlaps, and I understand why people connect my work to the Renaissance, but for me, this is not the reference point—or at least not anymore. I can appreciate that era of my work, but it no longer defines my practice. My influences are now broader and darker. I embody mid-century fine art, complemented by the surreal and grotesque visual language of the early 20th century. Much of my work is shaped by chiaroscuro and by capturing muted, earthy tones that softly echo the look of pigment degradation. That textured, rough, gloom-drawn quality comes from an admiration for images that feel touched by hand. There’s a possibility I am unconsciously paying homage to my past painter self. In my creative process, I’m continuously in a state of exploration that shapes how I interpret, portray, and tone my work. I think it stems from basic human curiosity; I have always been curious, and it’s foundational to my creative process. I’m constantly asking myself: What is the emotional weight and tonal complexity I want to express today, and what compositions am I working with?

Your subjects are often framed with a box-like composition. Is this a deliberate technique in your storytelling, or does it emerge organically in your process?

The box is a period of mine, and it became a staple fixture two years ago. I use the word “fixture” deliberately, as an amplification of my awe for it. It’s a very simple prop, but it has a certain longevity. There’s a mundane and ordinary straightforwardness I appreciate, and it holds space to be explored further. It’s little known, but I exist somewhere on the spectrum of autism. My mind intertwines with the compulsions of OCD, cleanliness, and the need for order. The box gives me this. It offers a bounded perception that allows me to enclose and frame something within a defined space. Growing up in Hungary and witnessing the post-communist upheaval, it became second nature to need boundaries, follow rules, and use order as a mechanism for living. Structure was vital and defined the very fabric of daily life. I like restrictions, and I like to be given rules, especially when working on projects. Organization, balance, and precision act as both a mental refuge and a way of navigating my work. In my recent work, you’ll see I’ve started painting a box on the floor. It creates an entirely new feeling—more spectral, airy, and effortless. I will continue to use this technique until it exhausts itself within me, and it hasn’t yet. Often, a client will suggest a different course, but if the idea still stirs something in me, then it continues to live. Watch me reshape it, reframe it, and reimagine it, and it will feel unfamiliar again, entirely renewed in its presence. The same applies to fashion. I have my patterns and my style, but I will make the models scrunch, grab, and pull the fabric into new shapes.

Do you ever imagine full stories behind your images, or do you prefer to let the viewer create their own interpretations?

That’s a difficult question—really difficult. I have passing thoughts, fragments of details, obsessions, and whatever is captivating me at that very moment. These are spontaneous impulses that I want to weave into something resembling a story. But they aren’t narratives; they don’t fully exist yet. My images are built in balance with what is felt. Tied in with my autism, I can become a difficult person because I still need restrictions. I’m a conservative Eastern European. There are only a few things in this world that I truly like, and this small bracket of interests, once combined, is powerful. Each detail has to be more than correct; it can come down to a strap on a heel or a fold in a coat. If I don’t like something, it’s dead to me. It’s gone. For viewers, everyone has the freedom to voice their opinion, and I like hearing what they think of my work. Sometimes I take in their input and form a conclusion; other times, I keep my thoughts to myself. If I’m being told what to think, I retreat and continue to create on my own terms.

What have you watched, heard, or read lately that has inspired you?

I recently spent 42 days in China, visiting the southwestern province of Yunnan. I wanted to see the layered architecture of these subcultures, which is why I traveled to Yunnan, home to a minority group called the Yizu, made up of the Yi people. I took my time, visiting remote villages and immersing myself in their customs. I was able to see how they make their clothing, which is rich in color and decorated with silver and handmade jewelry. I saw older women so elegantly dressed, wrapped in bright scarves and adorned with headpieces—and this is how they dress every day. I was shocked, in the best way possible. It was amazing, and I’m still at a loss for the right words to describe my experience. Being in Yunnan was an awakening for me. If you look at my work, you’ll see that I’ve always been very against the use of bold, loud colors. But after living among the Yizu people, something shifted within me. I can’t fully explain it yet because I still need time to process it, but I know it will definitely have some effect on my work. I’ve also been educating myself on folklore over the last two years, absorbing its traditional wares and culture. It may not show predominantly in my work, but there are elements and subtle styling choices that embody it. While in China, I collected an array of old fabrics, handmade hats from before the Qing Dynasty, and lotus shoes. Wherever I go, I look to preserve these folklore elements if I’m able to get my hands on them.

What do you love most about what you do?

What doesn’t exist, I create.

What’s something outside of your work that you would like people to know about you?

My mental state. As I’ve mentioned in this interview, I’m on the autism spectrum, and what most people don’t initially see—until it unnerves them—is that, in parallel, I’m stitched with threads of post-communist Slavic grit. It’s my internal architecture, and it defines how I see, feel, shoot, and present my work. A lot of people, upon meeting me, notice this oddity, this cuckoo “cuckooness,” before they see my artistry, papers stamped and madness certified. I’ve made peace with the fact that I unsettle people. My work wouldn’t be what it is without it.

Who’s one to watch?

Freddy Coomes and Matt Empringham. I am obsessed with their work; they’ve become my new favorite. Everything they create, I want.

Selected Work

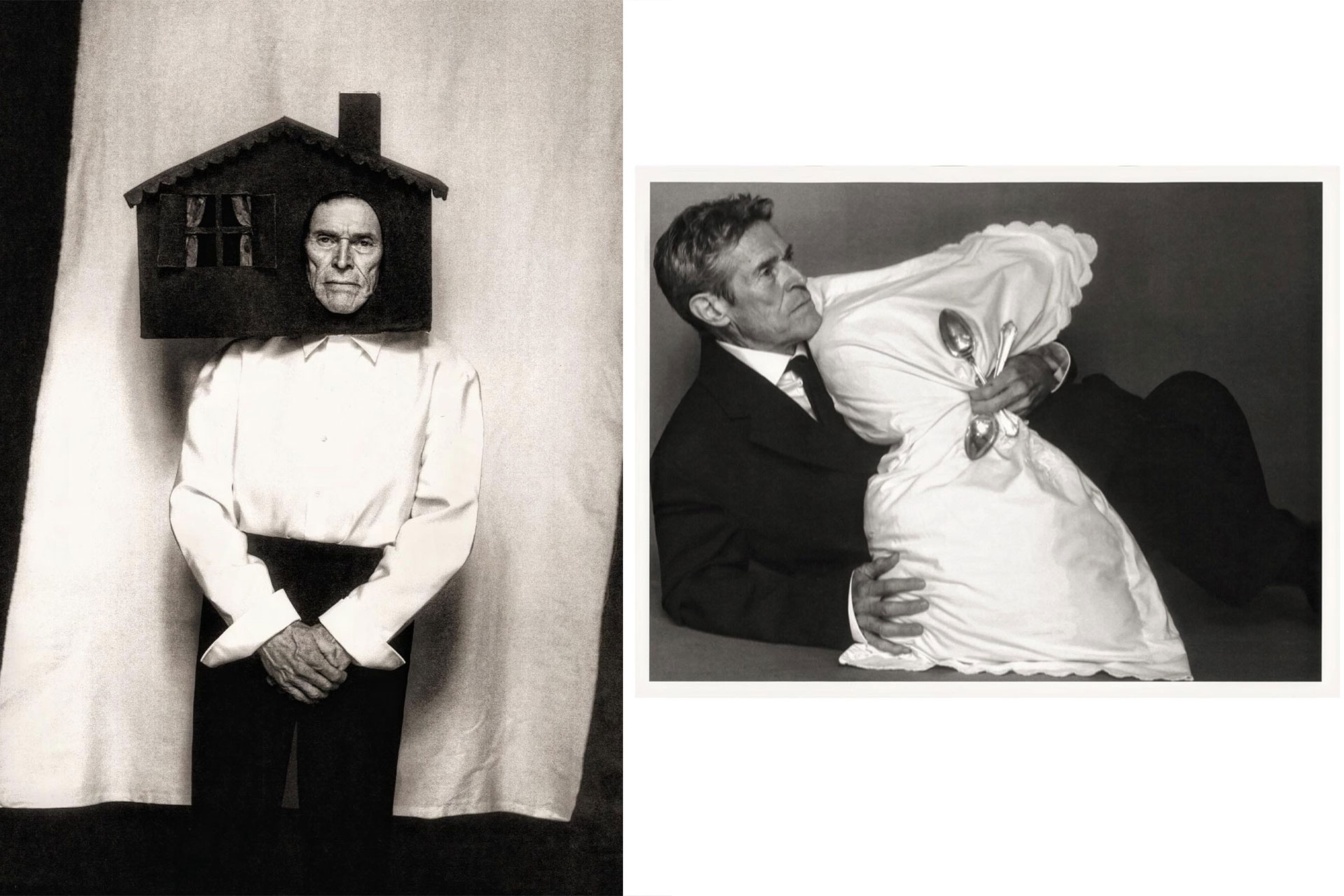

William Dafoe

William Dafoe, GQ

The shoot with Willem was a last-minute booking, and I had to travel from Milan to Rome to meet him. I was well-versed in Dafoe’s work, but at the time, I hadn’t connected his face to the many characters he’d played. On the day of the shoot, I was told the vision was simple: clean, standing in a suit, shot in black and white. It felt irregular to go that route. I wanted the images to go beyond the surface and symbolize the depth of his intellect and obsession with art. Willem Dafoe in a suit has been done a thousand times before, and I wanted to make this personal and carry the weight of who he is. Months prior to the shoot, I’d been back in Hungary visiting my grandparents. During that visit, my grandma and I were looking through childhood photographs, and I came across a picture of my kindergarten self with a cardboard house on my head. I vividly remember my grandparents’ disapproval of Farsang, which is similar to American Halloween but more like a children’s carnival with costumes. My very conservative Eastern European grandparents had strong views on how children should dress—elegant and smart. In dissonance with the celebration, they dressed me in my formal school clothes and constructed a headpiece resembling the house I grew up in. That’s the origin of the cardboard house headpiece. So, when I was photographing Willem, that was my vision: his head inside a house. I wasn’t sure if he’d agree, but I knew this picture would mean something, even if only to me. We shot in a botanical garden, a team of six, relying on daylight. There was no drama; it was very simple and familiar. I asked Willem to wear the headpiece and pretend his parents had just sent him to the corner for misbehaving. It was as if the air around him changed—he became a stubborn child, defiant. Three shots in, and I had the image. That picture became significant in my career, and it’s truly beautiful that it’s tied to my grandma and grandpa. This photograph holds immense depth for me. The house headpiece paid homage to my grandparents and the stoic beauty of my Eastern European upbringing. Willem channelled the character of a stubborn child, and the beginning of my fixation with a face placed inside a house. There’s a story behind the placement of the spoons Willem is holding in his hand on the left image. As we were shooting in Rome, the crossed spoons served as a quiet nod to the Vatican.

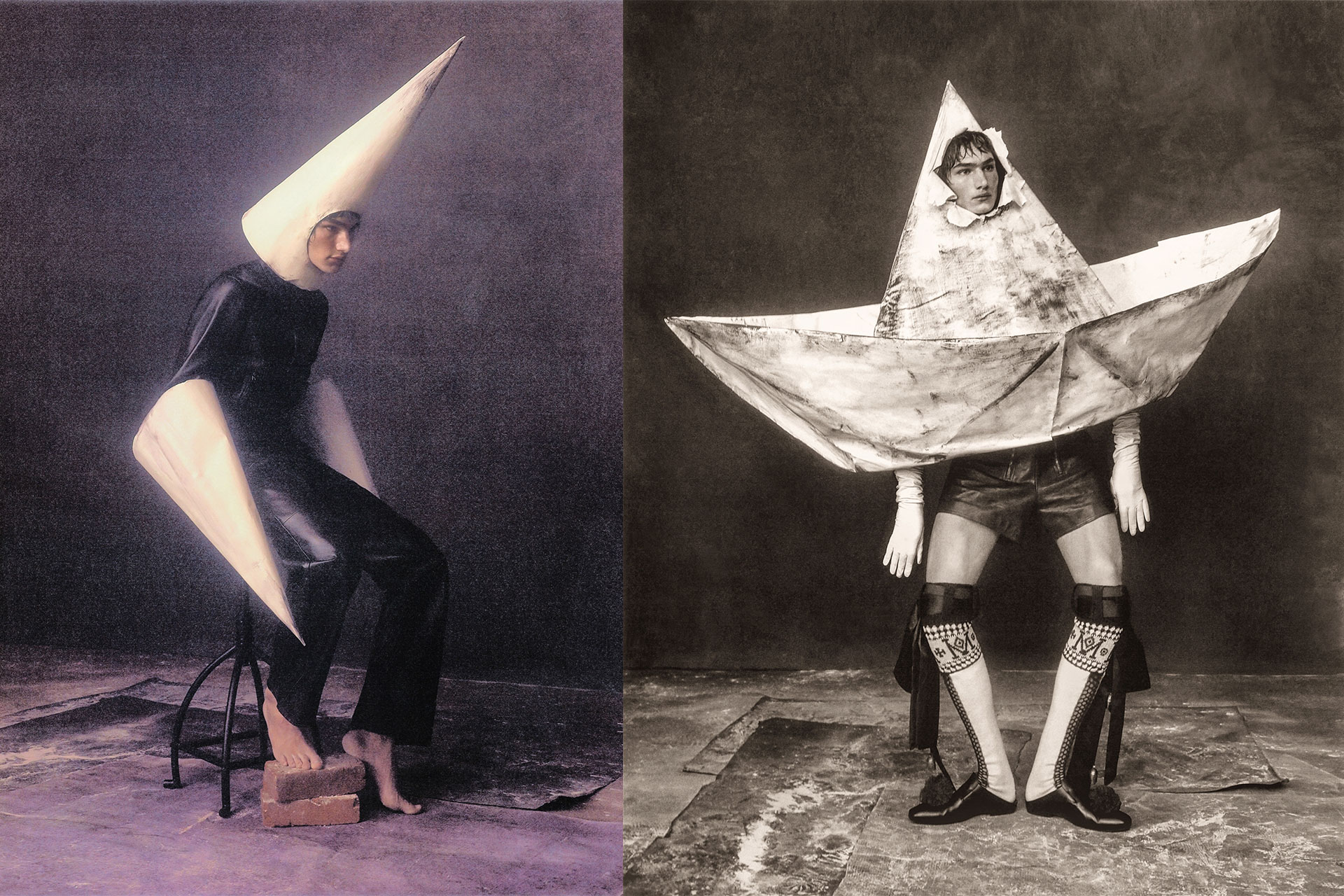

Silas Lutz Fabian

Veni, vidi, vici, Hero Magazine

The image on the left is when I began exploring cubism, an early 20th-century movement. I played around with geometric shapes and loved how they never quite matched but met. I also began to experiment with muted, monotone colouring here. The image on the right was ‘a love letter to a loved one,’ the boat symbolizes how the letter was delivered overseas. I see this series with many elements: it’s periodic and symbolic.

Personal project

This was a personal project of mine. I was fixated on his look, an albino Chinese man. On his head he wears a 100-year-old tiger hat, a 19th-century antique from the South of China.

Lorna Foran

Monsoori Couture Campaign

This is from a commercial shoot a few years ago, when I was capturing the Renaissance quality in photography.

Hyunji Shin

La Clef Des Songes, Numero France

I fondly remember working on this set, and it was very interesting. A unique technique was applied to create the outcome you see: layering images within images, keeping the previous images to fill gaps and spaces. Oh, and this Loewe coat—I still think about it.

Yura Romaniuk

Le Petit Prince, Numero France

Yura in a box. This shoot felt very natural to me; the pursuit of a simpler set design and imagery was peaceful.

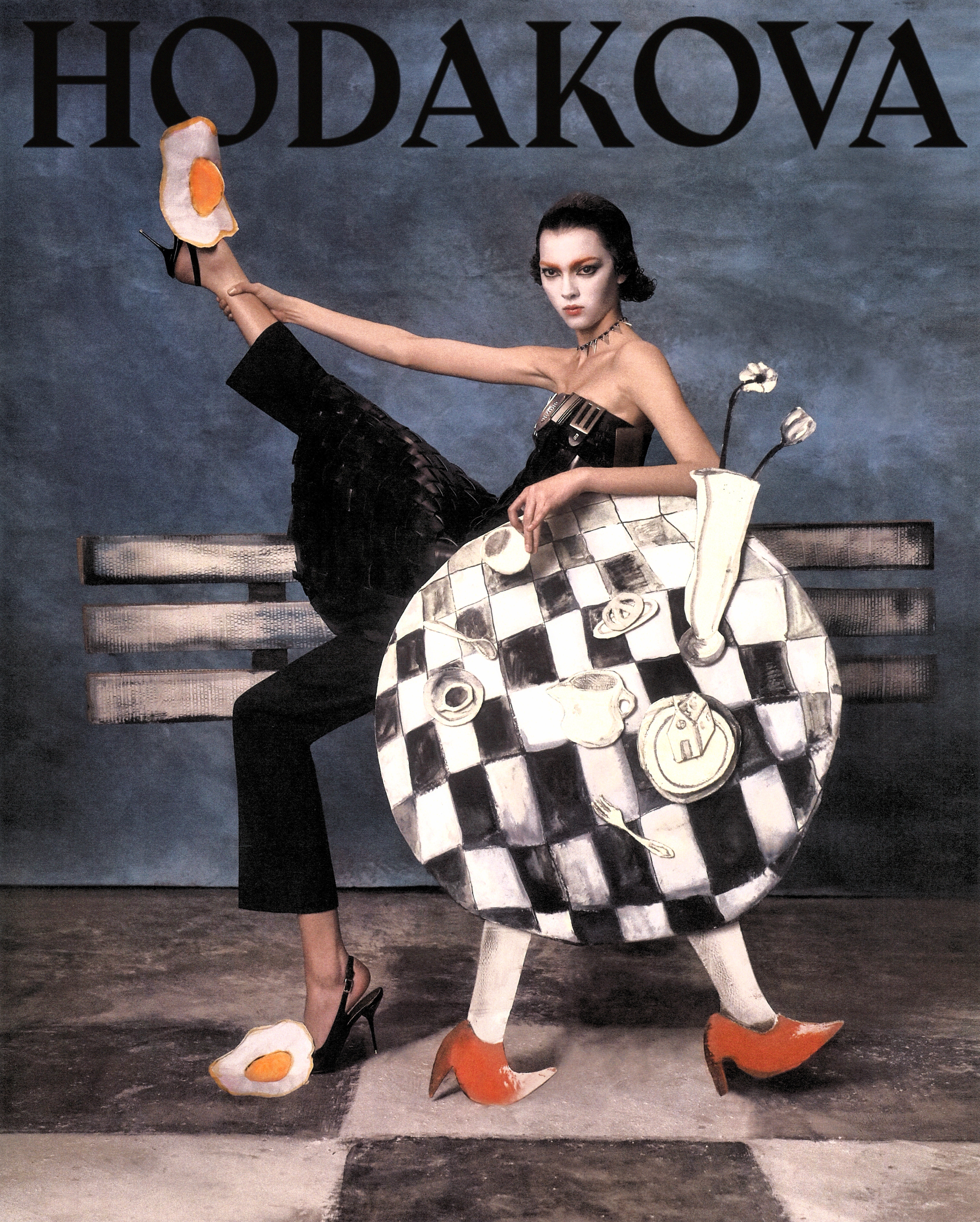

Nariah Nicolle

Hodakova Spring/Summer 2024

My vision here was to create a mixed perspective, amplifying an irregular world. At this moment, my obsession with cardboard began.

Cate Blanchett

Follow The Penny Walks, Vogue China

I love this photograph. When I look at this headpiece, I see my staple in its truest form. Vintage brutalist architecture.

Ateta Jok & Nyakong Chan

Exercices De Style, Numero France

For this series, I return to using mixed perspectives, newly calling upon nostalgia and the connection between two people. Again, you see my cardboard props – simple resemblances of everyday life.