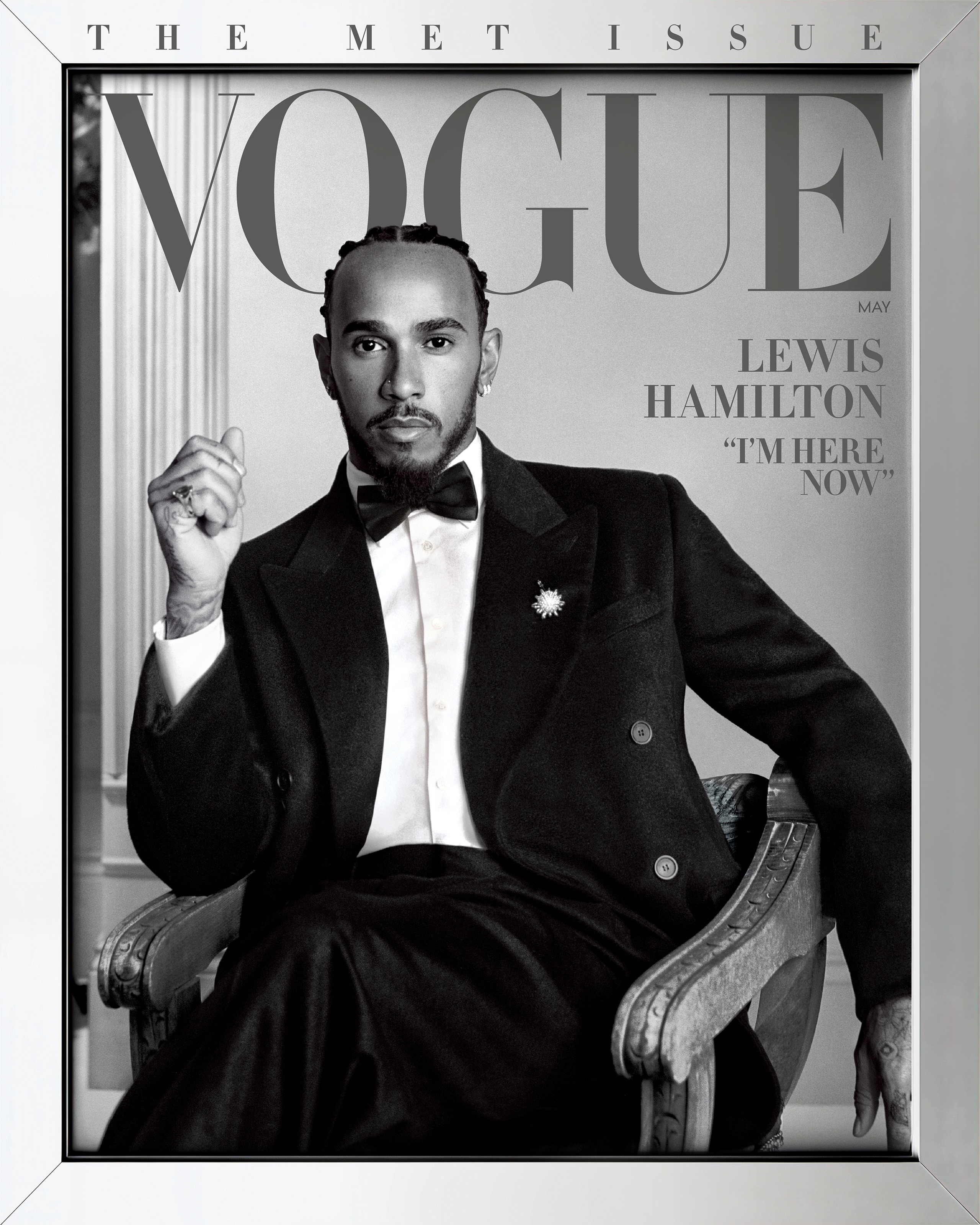

With over 15 years in the fashion industry, stylist Eric McNeal has cemented his place as a visual storyteller who moves with intent, reverence, and care. A Bed-Stuy native with Southern roots, McNeal’s work exists at the intersection of history and imagination, where styling becomes a quiet ritual, a cultural archive, and often, an act of ancestral homage. From styling editorials for WSJ, GQ, and his May 2025 Vogue cover with Sir Lewis Hamilton—his longtime client and collaborator—to working alongside brands like Louis Vuitton, Pyer Moss, and Wales Bonner, McNeal’s practice is far deeper than the aesthetic. Models.com contributor Shelton Boyd Griffith caught up with McNeal to talk about stillness, this year’s monumental Met Gala, and Black legacy.

Let’s start from the beginning. What was your earliest connection to fashion?

My earliest memories really came from home. I grew up in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, but I spent most of my summers in Gaston, South Carolina. My aunt had an atelier, though I didn’t know that’s what it was at the time. She would make clothes for folks in the neighborhood. Watching her work and witnessing that transformation through craft—those early impressions stuck with me. And then there were the men in my family. Their rituals before church, laying out their clothes the night before, polishing their shoes, spraying cologne. There’s something powerful in those quiet moments. As a kid, I didn’t realize it, but those were my first style references. That was my introduction to fashion—through family, through care, through the everyday.

Do those early rituals show up in your work today?

Yeah, they do. I’ve always been obsessed with the mundane existence of Black life, because how we show up in the world, how we live, is endlessly inspiring. We’re not a monolith, but we have this shared culture of showing up with pride and intention. Where I grew up, you had to match. You had to be sharp. And in the South, you had to look your best—everything ironed, polished. That still lives in me.

Adrienne Raquel for Brother Vellies Pre-Fall 2020 Campaign | Image courtesy of Permanent Press Media

Describe your creative process—how do you stay grounded when the internet is always “on”?

Stillness is essential. I disconnect a lot. I don’t really engage much on the internet because I want my ideas to come from inside. I walk a lot. I listen to jazz. I sit on trains and just watch people. That stillness is where stories come from. Like the Wall Street Journal story I did with Bolade Banjo—that idea came from a simple conversation about how we watched the men in our families get dressed growing up. The way of getting dressed was a kind of armor, a confidence builder. That’s where the work comes from for me. The internet can trick you into thinking creativity is a race. But originality comes from real observation, real silence.

“The internet can trick you into thinking creativity is a race. But originality comes from real observation, real silence.”

What’s currently inspiring you—visually, emotionally, spiritually?

Right now, I’m in a season of tenderness. I’m drawn to things that feel a little bruised but still shine. I read a lot. I write poetry. I’ve been working on a zine that’s taken shape over time. I just finished Breathe: A Letter to My Sons by Imani Perry, a letter to her sons that really stayed with me. It’s about how we present ourselves to the world, especially as Black people. That really hit me. I’m inspired by restraint. By people who don’t ask for permission. I love things that linger—jazz, poetry, physical archiving, watching documentaries like Ailey. That kind of soul work is what keeps me going.

Let’s talk about your first Vogue cover. That was such a powerful moment. What did it mean to you?

It was surreal and humbling. You have a Black man on the cover [Lewis Hamilton]—styled by two Black men [including Ib Kamara], photographed by a Black man [Malick Bodian], wearing Ferragamo by Maximilian Davis. That’s not just fashion. That’s legacy. Every time I see it, I think of my younger self and I think of other young Black boys seeing that image and realizing what’s possible. The whole production was a Black collaboration—from the styling and photography to the set design. It was a cultural conversation. It’s something that’s going to be in the library, and also something institutional, because it’s tied to the Met, so it’s a bigger thing; bigger than me even, but it’s something I’m really just grateful to be a part of. It reminded me that we don’t always get these opportunities, so when we do, we have to pour everything into them. To be seen and felt by your peers or by just your family, really, because, you know, it’s Vogue so to have that by your name, in your legacy — it really is something that every time I think about it, I can’t believe that I’m a part of it. So to have this,makes me so happy.

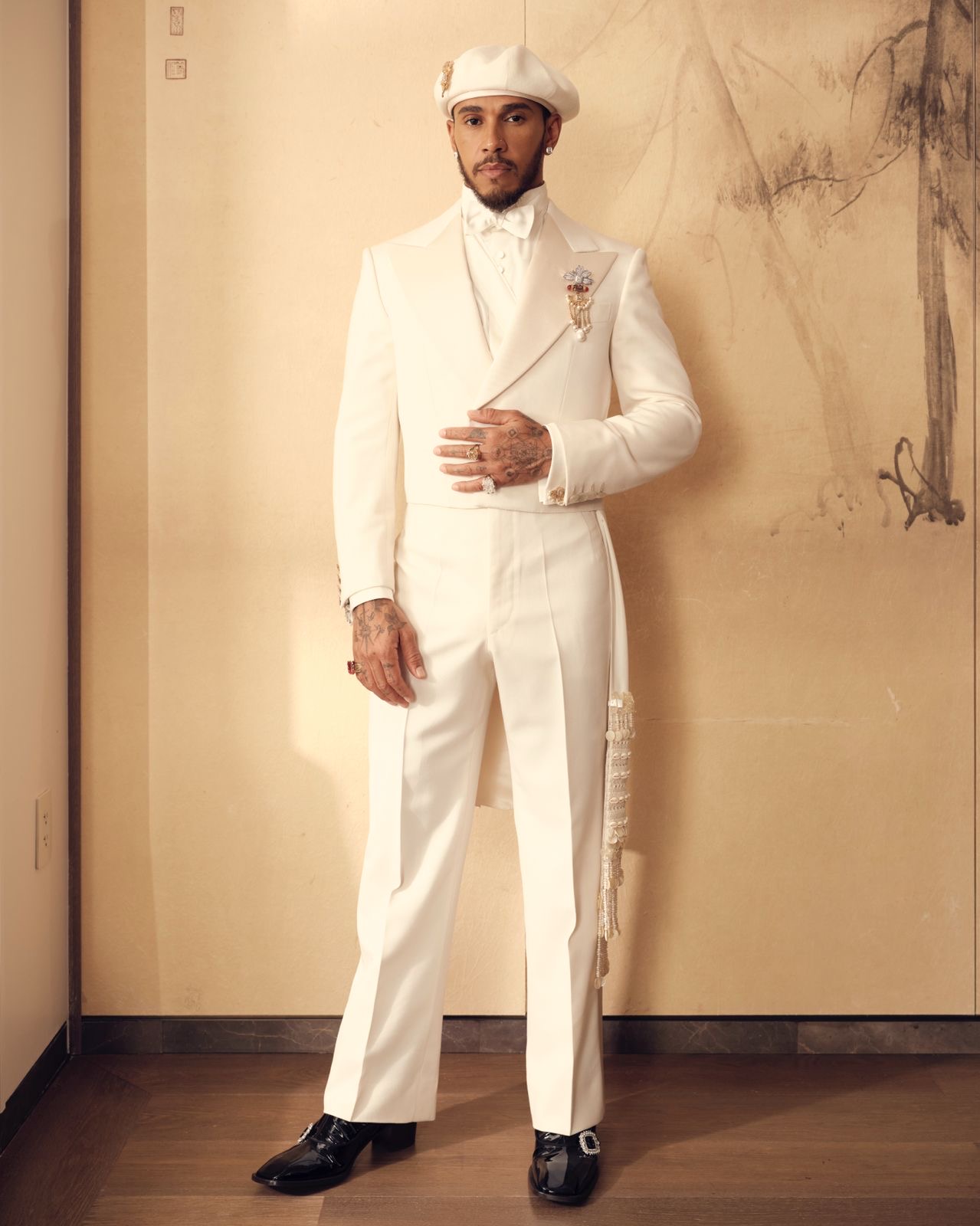

You also styled Lewis Hamilton for the Met Gala with Grace Wales Bonner. That look felt like a moment of fashion history. What was the intention behind it?

That collaboration felt like building an altar. Grace and I are both rooted in reverence—for craft, history, and Blackness. We didn’t want to make noise. We wanted the look to feel timeless. Intentional. Ancestral. We researched across the diaspora. Cab Calloway, Barkley Hendricks paintings, cowrie shells, the power of adornment, the purity of the color white. It became about using Lewis as a vessel to honor our lineage. And Lewis brought so much presence and trust to that look—he allowed the story to live. That was the first time I got to do ancestral work in a deep way. It’s one of my proudest moments. Grace is somebody who has so much intent, Lewis is such an intentful person, as am I so the collaboration, really felt like we all were like in school. Once the announcement happened, I was a student of Monica’s [Miller]. I lived with that book (Slaves To Fashion). I love history —it’s my best friend — so, the fact that I got that access to Monica and Andrew Bolton, having them, really helped me a lot. I would go and sit with them and talk about what I was trying to do. “Okay, well, I’m trying to tell this story about cowrie shells.” “I’m trying to tell this story about this flower from Grenada, or this specific thing.” And when you have, the very people from the institution, people who are professors, you can’t fail really, when you have the resources right in front of you. I was so grateful to have them to kind of just keep going back to and being like, “what is the significance between the beret and Blackness?” It was so great to have those conversations, and I think that’s what the Met Gala is about. The Met is about somebody giving you an assignment, and you taking that assignment and you interpreting that for what that means to you and what that means to the person that’s kind of conveying the message, which is usually the talent.

Photo by Miranda Barnes | Image courtesy of Permanent Press Media

How do you decompress after a shoot/project?

I always have to recharge after the thing. You know, it’s such an emotional, vulnerable thing making work. I think we like to act like it’s this confident, fab thing, but it’s insecurity that kind of drives you and that output of work. But once you put out the work, it’s no longer yours, so you really have to protect and always try to come back to yourself.

You’ve always worked closely with Black designers—Aurora James, Kerby Jean-Raymond, Grace Wales Bonner. That’s been a throughline in your work.

It’s intentional. We didn’t grow up with many Black-owned brands. So being able to collaborate with Kerby, Aurora, Grace—it means a lot. I see myself in those brands. I know they care and I love us. Like, I really love us and that love shows up in the work. When I was working with Kerby on those early Pyer Moss ads—going to L.A., Chicago, talking to people like Angela Rye and Dr. Nadia Lopez—those are moments I’ll never forget. Or with Brother Vellies and Adrienne Raquel and Anok Yai during the pandemic—just asking Anok, “How do you want to feel in these shoes?” And she said, “Sexy.” So, we made that happen. It was organic, rooted in trust, and in feeling each other. Working with brands that reflect our values and speak to our communities, it’s a gift. Black designers and Black brands are the future. Period.

What advice would you give to aspiring stylists?

Protect your perspective. Don’t be afraid of the process; it’s where your voice is shaped. I assisted for maybe eight years, maybe more. And that time grounded me. Also, someone once told me, “When the elevator goes up, always remember to send it back down.” That’s what I hold onto. You don’t arrive alone. Send it back down for the next.