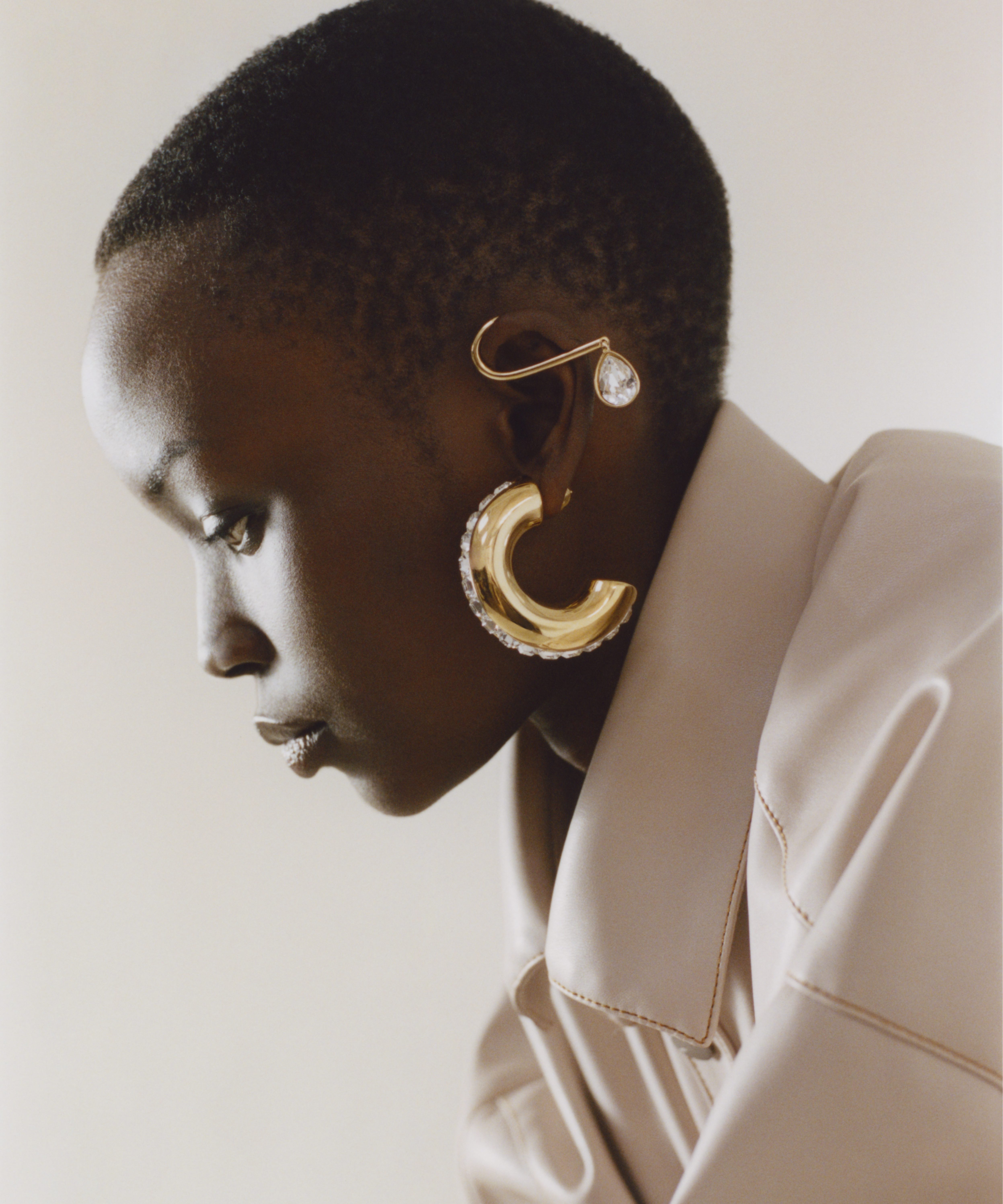

Lucie Rox for NET-A-PORTER | Courtesy of Engineers Of Change

The subtle introspection that comes across in Lucie Rox‘s work tells a story of women who celebrate the world around them, whether it’s a Roman landscape or an exotic flower field. The French-born fashion and landscape photographer, currently based in London has steadily made a name for herself working with indie magazines and big commercial clients alike like Muse Magazine, Fenty, Loewe, and Peter Pilotto. Playing with deep shadows, close crops, and flushes of delicate color, Rox’s best work makes her subjects take on an ethereal quality rooted in the modern femme. Now having gone through quarantine and the protests centered around Black Lives Matter, Rox has recentered her focus on being resolute in her creative vision, organizing to raise awareness on racism and domestic violence, and dismantling misogynoir. Models.com spoke with the promising photographer about her transitional beginnings, rejecting compromise, and battling implicit racism in fashion and beyond.

How did you first get your start in photography? Did you assist anyone early in your career?

I picked up my first camera in my early teens – I think it was a Christmas present. It was a really basic and cheap little compact digital camera but I started using it all the time to document my life, shooting my friends and places I would go to. At first, I got into the documentary aspect of photography & became aware of Magnum Agency when my step-dad got me the Magnum Magnum book which made a great impression on me. It’s only later, in my late teens that I became captivated by some fashion imagery, following my curiosity for the surrealist movement and discovering the images of photographers such as Man Ray, Lee Miller, or later on, Sarah Moon. Music was my main passion since childhood, so I started mixing both my interests and got into shooting bands & live shows. I worked for a few different music magazines as a teenager and when I was living in Paris as it was a fun way to get into all the shows I wanted to go to for free and that’s when I started taking photography a little more seriously.

I didn’t study photography. I never finished my Literature & Arts degree and moved on a whim to London after luckily failing to get into Photography School in Paris – so I started working in studios and assisted a lot of photographers when I first arrived in London a little over 7 years ago. I always kept shooting my own work on the side but I am very grateful for all the experience I got while assisting. It taught me a lot about lighting, but also about the business side of the industry, how to be on set and deal with clients, and also how to deal with misogyny in the industry.

When you’re working on stories, do you think of commercial success? Is that a focal point or is it more important to nurture your artistic point-of-view?

The more I grow in that practice, the more I try to stay away from thinking about commercial success. At the beginning of one’s career, it’s very easy to get influenced by what other successful photographers are doing & to unconsciously mimic it as you are yearning for success or recognition yourself. But I do think focusing on that is detrimental to the work, and the more important thing is to try and nurture your own vision, figure out your own voice and way to use it. In the age of social media & rewarding success based on how quick it happens, rather than on how sustained your point of view has been it’s very difficult to put this mindset to a distance but to me, it’s essential. The pressure for success and status is as constant in this industry as it is destructive. Even if you don’t want to think about it, the politics always gets in the way and you have to juggle parameters. Is it a good look to shoot for this magazine? Even if I have complete creative control is that gonna be detrimental down the road? It’s hard to remove the commercial success out of the equation 100%, we all aspire to success and need to make a living, but I try to keep it as far as I can from the creative process.

Where do you go to source inspiration or find references? What drives you creatively?

Inspiration comes from multiple and diverse places. The more I work, the less it comes directly from photography. Usually, the source comes from something else, it can be a movie, painting, an abstract idea or a moment. Lately, I’ve been very much inspired by poetry and writings. I always find the result more compelling when I start the process by looking at other mediums; it allows space for me to figure out my own look on things rather than unconsciously copy things I’ve seen before. The research process usually is about following the thread backward, from this small moment that might have captivated me and sprang an idea, to finding the visual references that echo what I have in mind so I can clearly communicate with my team. I love digging through photography books; my own, at a library or a bookshop, and also through archives online and it is still an essential part of finding references. Really anything can be a reference, I guess where it’s interesting is what you do where all these references are crossed.

Lucie Rox for Pleasure Garden | Courtesy of Engineers Of Change

How do you choose the stories you work on? Are there any important factors that must be in place?

For editorials, there are always the same basic factors that I think about before accepting a commission: what is the publication, creative freedom, team, & budget. Most of the time editorials don’t have a budget or very little and as a photographer, you are expected to pay for most of the production costs so it’s a very big investment in terms of money. I can only afford to do a limited amount each year (some seasons I haven’t be able to afford to do any), so I have to make sure that if I work on a story it is for a publication I like, where I’ll have the creative freedom to create the story how I want it and that I can work with the team I choose to. There needs to be as little compromise as possible on my part.

How has the experience been working with clients around the world and what moments have stood out as memorable?

I feel very blessed to have been able to do so much already early into my career. If you’d asked me when I first arrived in London 7 years ago, I couldn’t have told you that I would travel that much for work, or that my client list would have included brands such as Loewe, Givenchy, or Fenty. One moment that keeps coming back in my head lately is traveling to Rome for my latest story for Pleasure Garden. I was commissioned by the magazine to shoot a story, part fashion in London / part landscape at the Villa d’Este near Rome which is known for having a lot of incredible fountains. The source of my inspiration for this story was a poem by the great Audre Lorde ‘From the House of Yemanjá’. Yemanjá, is a Yoruba divinity, goddess of the oceans, mother of the other Orisha, and it is said that rivers flow from her breast. I had no idea but when I arrived alone that morning to the then empty villa, I realized that multiple of these Roman fountains were female figures pouring water out of their breasts. This abstract and unexpected connection between all these places and spiritualities somehow made this day and whole shoot so special to me.

Lucie Rox for SIGNS | Courtesy of Engineers Of Change

You made a zine last year called SIGNS documenting your travels through Japan – what inspired you to first visit that region and document your experience? What does SIGNS mean to you?

I have been wanting to visit Japan for years, and me and my partner decided to take a trip there across Christmas & New Year 2017 as a holiday. I love traveling for a few weeks at a time, and going from one city to another in that time frame – it’s my favorite way of discovering a country or region. SIGNS came together a little bit as an afterthought to be completely honest, I didn’t really go there thinking I’ll make a zine out of it but documenting my travels is just a habit now. I always take a camera with me & shoot as I go along. Having a camera on me instantly makes me more curious, inclined to observe, and look for the little signs of some sort of beauty.

The title SIGNS came from Roland Barthes’ Empire of Signs. Barthes wrote about his own observations while visiting Japan, and wrote that even if the book is set there he “has never, in any sense, photographed Japan. Rather, he has done the opposite: Japan has starred him with any number of “flashed”; or better still, Japan has offered him a situation of writing” acknowledging his position as a western white man. For me, SIGNS encapsulates this idea of acknowledging our position as photographers, we can only capture signs of something, sometimes they are pointed at something we know and understand but a lot of times their meaning exceeds our own limited vision.

Lucie Rox for Sixteen Journal | Courtesy of Engineers Of Change

An image of yours was featured last year in The New Black Vanguard exhibition, why do you think acknowledgment and support of different perspectives are so important if fashion is to survive?

I don’t just think it is important, I think it’s overdue. Fashion has been profiting from black bodies, black talent, and black perspectives forever, not only does it need them to survive but fashion needed them to be able to exist in its current form. At the age where all brands and influencers are making money on streetwear, trainers, and blackfishing it is about time fashion starts acknowledging & supporting black artists and more importantly starts redistributing the wealth and opportunities to the community they’ve been stealing from. But this acknowledgment cannot be done in the form of tokenism and that is why I am again so thankful to Antwaun Sargent for putting together this book and exhibition, for us, by us. The opening night was such an incredible moment of black creatives coming together to celebrate themselves and to show the world that we do not wait on them to give us a seat at their table – we’ve brought our own table and we’ll have that conversation on our terms. For me, that’s how real change happens.

What has been your experience navigating the fashion industry as a young woman of color?

Being a woman in this industry is hard. Being black in this industry is hard. Being at the intersection of the two is, you’d guess it, hard. Being light skin and cisgender, I am in a better position than a lot of dark-skinned women, but having to navigate sexism, racism, and also classism which is strong going in society – why would fashion be an exception? It is an exhausting experience. There’s a lot of power dynamics already at play when you are just starting out, and it is an industry where offending the wrong people could cost you a lot in your career. Navigating this as a black woman means that it is even harder to speak out or confront forms of misogynoir because of the fear of it costing you your job. Often, I’m the only black person in the room, so it can feel like a pretty isolated position and a very difficult one from which to be heard. It’s easy to feel powerless and that you have to remain silenced as people will rarely stand up for you and that form of racism is so normalized that people will not see what the problem is.

“Don’t be afraid to tell your own story and to channel your own experience in your work, but also, question your own gaze and how much of a white/male gaze you’ve internalized and are repeating.”

How have you been finding ways to use photography as a creative outlet during times of isolation?

I haven’t. I’ve spent most of my isolation time not using photography at all. I don’t think I’ve picked up a camera once during this whole time and it has been incredibly beneficial to take that break. For a long time, I was connecting most other activities that brought some kind of artistic and intellectual stimulation with my work. Every book I’d read, movie I’d watch, or exhibition I’d see would become something that could be used as inspiration or reference for a shoot; art had become really utilitarian & only seen through a productivity lens and as a consequence, it became really hard to organically connect with it. Isolation has been a great time for me to find pleasure again in all of these things and also to be able to recenter on the things that are meaningful and actually urgent like organizing politically and getting involved in more activism.

The other thing lockdown has allowed me is to rethink the way I see time and the creative process. The way the commissioning process works in the industry doesn’t allow much room for failure: if you commit to shooting a story for a magazine and you spend a lot of money on it, it has to be good straight away. During isolation, I have been enjoying escaping this dynamic and learning how to fail again and how important allowing failure is to the creative process. I have been experimenting with new techniques and mediums just for myself and I’m getting very excited about the idea of taking the time to build a practice rather than always aiming for immediate results.

Lucie Rox for FENTY | Courtesy of Engineers Of Change

How have your experiences as a black woman influenced your gaze and perspective as a photographer?

My perspective as a photographer is completely intertwined with my experience as a Black woman whether I want it to or not. I don’t think you can ever completely remove your own identity from your “gaze”, that’s the same reason we talk about the “white gaze” or “male gaze” and it is biased by the experience of being part of the oppressor group and these dynamics of power. As a Black woman and as a woman of mixed heritage who grew up in a predominantly white environment, my work is a testimony of my own journey towards accepting my own Blackness and of my own political education and growth. “Black is beautiful” is still such a powerful statement because we still live in a society that makes us believe otherwise. This constant hit to our self-esteem is just one way in which white supremacy deprives us of our own power and maintains our oppression, and I’ve worked very hard in the past few years to reclaim that power back for myself. My work has been one of the ways of doing so. However, as members of the diaspora our own history, identity, and heritage is often fragmented or inaccessible; by way of colonial erasure and by society’s racism which has forced many of our parents to “assimilate” and deny their own culture as a survival technique. That means that most representation of yourself is still filtered through a pernicious, white, colonial gaze (and in fashion, where black bodies are still often only used as props, this gaze is still very predominant). I still have to constantly question my position as I still do my own identity while I’m still trying to detangle all the threads and try to separate my own vision from my own internalized white gaze. It’s a constant, difficult but necessary unlearning curve.

I saw your amazing initiative to raise funds through print sales for Solace Women’s Aid Emergency fund, why did you decide to join this cause?

Having been a witness of domestic violence in my own family, when lockdown started I couldn’t help but think about the women who will be stuck 24/7 with their abuser for weeks, with very little means to escape. The data also came out very quickly after the beginning of lockdown, on charities and grassroots organizations warning about a very important surge in calls for help and their lack of funds and means to respond to this surge. A friend recommended Solace as they’d been helped by the charity in the past so I decided to reply to their Emergency Fund with how I could help, having myself no income during lockdown. Since the beginning of lockdown and the launch of this fund, domestic violence has risen by over 20% and killings in the UK have doubled compared to the same period outside of lockdown. At the same time charities still need to rely on the community rather than the government who is not showing up to do the work – once again we are the ones having to step up. We’re seeing this again in London with the case of Sistah Space, a space supporting victims of African-Caribbean heritage, that is being displaced to an unsafe building by the Hackney council. They are relying on their community through fundraising and protests to try and save them. Supporting this cause is an immediate necessity.

Lucie Rox by Chloe Le Drezen | Courtesy of Engineers Of Change

What is your advice for women who want to make a career as a photographer?

Ask yourself: how will a cis white man act in this situation? What would he request? And don’t be shy to demand the same with the same amount of confidence because you deserve it. Refuse to be underpaid & don’t be afraid to say no as long as you can afford it. If you ever feel like there’s no space for you in this industry, create a new space. Start your own projects, zines, communities if you feel left out, and invite your peers to work with you. Foster your own circles and connections with the people that will support and understand you. Friendship with other female photographers has been a great source of strength and power for me, and such an important support system to navigate this industry so I’d advise cherishing these connections. Don’t be afraid to tell your own story and to channel your own experience in your work, but also, question your own gaze and how much of a white/male gaze you’ve internalized and are repeating. It’s a long, maybe infinite process but it’ll help to find your own genuine voice and stand out.