While once fashion images would arrive neatly bound in a glossy monthly burst, now they are dispatched from all angles, all of the time. Faced with this deluge, audiences are hyper-alert to inauthenticity, communicated by the uncomfortable crook of an elbow or an awkwardly held pose. Which is where movement directors like Emma Chadwick come in.

Born and raised in London, as a child Emma’s irrepressible energy led her mother to put her in every class she could find. She was dancing from the age of three and training professionally from 12, learning classical ballet and modern contemporary movement, but also hip hop, flamenco, tap dance. At 19 she moved to Switzerland to join the Ballet Basel, before touring the world with Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake. It was on returning to London as a freelance dancer and choreographer, where she was first approached to work in fashion and advertising images, that she began to move towards movement direction.

Now, Emma works across photography, moving image and live performance, coaxing authentic physical expression from models and dancers, but also from sportspeople, politicians, actors and many others. Recent projects have seen her collaborate with the likes of Proenza Schouler, Adidas and Louis Vuitton, and publications such as Vanity Fair and Vogue. We sat down to discuss the importance of movement to a fashion image, her process, and why the runway finale is so hard to get right.

Text and interview by Maisie Skidmore for Models.com

Images courtesy of Streeters

How do you define what you do?

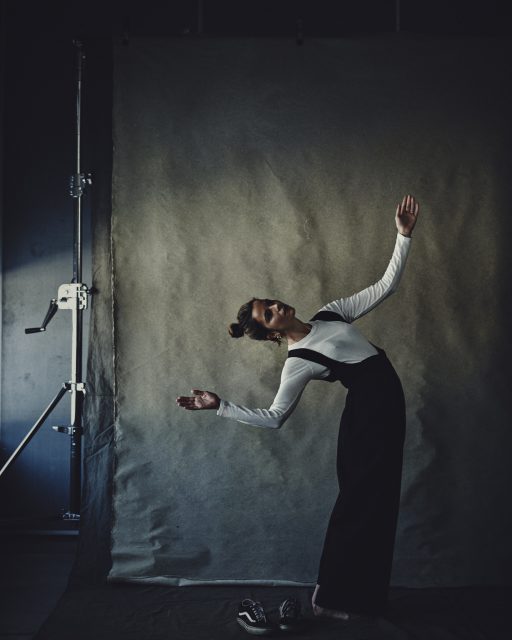

It can be something as simple as understanding what moves people. Say, you have a model who needs to move euphorically––connecting with that euphoria is different for every individual. I find ways to help them understand their physicality, to feel good within their own bodies, to move in a very high-pressure environment. If I’m working with a dancer, the movement direction becomes much more honed. We might need to problem-solve––say, how can we make a really beautiful pile of bodies, and the person at the bottom isn’t gonna die? It’s a mixture of working closely with the individual to find ways to push their natural physicality to a place of curiosity, or abstraction, and problem-solving for new, different and interesting ways to view the body.

So that process caters to each individual.

Exactly. A lot of the time in fashion, there isn’t time for trial and error. You need to perform immediately, in the moment––you’ve got 15 shots to get in a day, so you don’t have time to warm up for three or four. Every other role within a fashion shoot is so heavily planned and so meticulous, but somehow the physicality of the talent often gets left to the last minute.

Where I can, I take the time while everyone else is setting up lighting and talking through creative, to get to know the talent, to understand what’s going to make them feel great, make them move in a way that best serves the creative. Collaborating with that person to make them feel that their voice is heard is super important, for physicality; you can see in an image if somebody feels uncomfortable.

When it’s more dance-heavy, then it becomes more about the details of the physical body, and how you can help somebody understand the tiny nuances that are really going to affect an image. No two days are ever the same, because you’re always working with different personalities, different body types, and different ways of thinking. It’s constantly evolving.

What do you think precipitated this role?

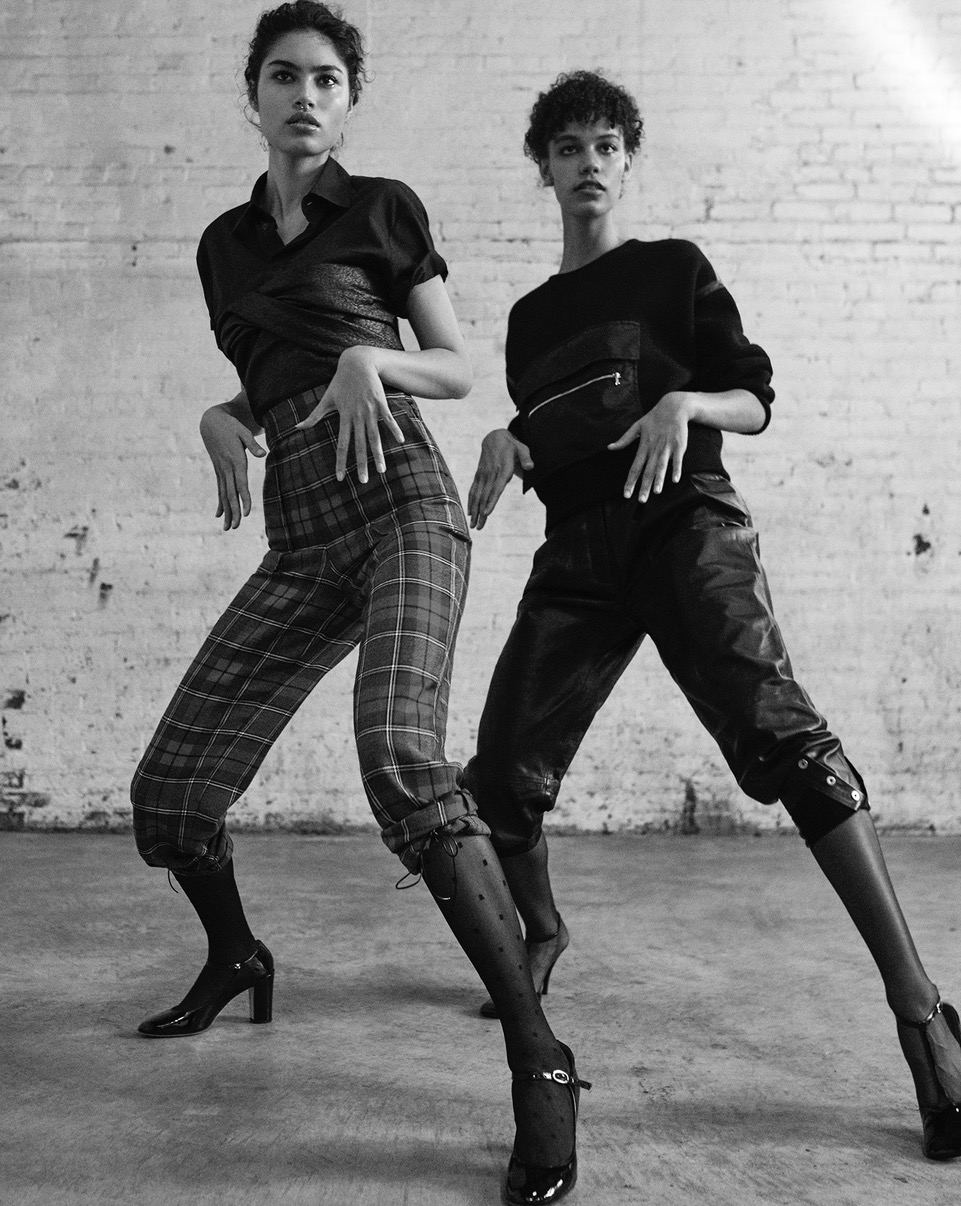

Movement has always played an important role in making great images legendary. But there has been a shift in the way we view fashion––through social media, through websites, through video content, but also just the sheer volume of advertising and fashion that we see on a daily basis. We’re consuming so much more than we once were, and that has meant more is being asked of what is produced. At the end of the day, clothes are going on the body, and the body needs to move in a way that makes the fashion come to life.

Movement is a tell-tale sign of authenticity, isn’t it.

Totally. You can read immediately if somebody is uncomfortable. And maybe that’s what you’re going for, but they have to look uncomfortable with conviction. You have to know that they understand why they’re doing it. Taking the time to concentrate on the physicality already affects how the body moves; you’re giving somebody the freedom and the time to be authentic, within a very high-stress environment.

Nars Cosmetics by Fabien Baron

Have you ever struggled with stepping out of the limelight?

I actually find myself to be more creative working on other bodies than I do on my own. I still dance, and I think it’s important as a movement director and as a choreographer to still work on your own practice. But I find I’m more accepting of other people’s ways of moving, funnily enough. It’s been a beautiful transition, actually.

As a dancer, there’s a lot of internal learning, because it’s about figuring out your own way of moving and honing that. Now, so much for me is about looking out––coming up with references and ideas, how can I inform and enhance an idea, and how can we transpose that onto another body? So it’s much more external.

As a dancer, you don’t vocalise very much. You’re told what to do a lot. And a huge portion of what I do now is about talking to people: “Yes, brilliant, move this way, keep the body flowing, what does it feel like, how is the space behind you, what would it be like if somebody poured a glass of water over your face right now?” I’m throwing out ideas the whole day, to help people get out of their own headspace, and giving them new ways to contextualise movement. I do miss the rush of performing within a theatre environment, but then I get that working on shows.

What does working on shows entail?

A lot of the time, so much goes into making these shows perfect, and then what the models are actually doing on the runway is written up on a board for them to read the moment before they go on. That’s just not going to cut it, as far as making the show look cohesive and nuanced goes. Something as simple as the spacing and timing of models in the finale [can change everything]. I worked on the Proenza show both seasons last year. They’re often very simple, but very specific. Because they wanted it to be very linear, I cued the models with the music, so everybody was entering on the music at a specific time, with the same distance between them. It just makes the show, and the collection, feel well thought-out.

A lot of people now want more performance within their shows, so it’s about seeing where you can take that. I worked with a dancer for the F/W19 Ryan Roche show last year, and we choreographed a beautiful entrance. It really affects the space that the viewer is entering into the collection with. In a world where everything is Instagrammed and Facebooked and Tiktok’ed, it’s about finding new ways to make people go “oh god, did you see that show? That dancer was amazing.” It changes the conversation.

Missoni x Adidas by Santiago & Mauricio Sierra

Where do you look for inspiration?

I always tend to come back to the dance scene in the 1970s. Some of the great choreographers of that day were collaborating with artists, musicians, architects––you have people like Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, Michael Clark. These visionaries who were pushing the boundaries of an art form that was still very ballet-heavy. They all collaborated in such a natural and authentic and beautiful way. For example, with composer John Cage – something as simple as taking a piece of his sheet music, and looking at the notes on a page, and turning them into a floor plan for a dance. Whether it works or not, it was a place to start a conversation about movement that hadn’t happened yet.

I also love looking to architecture, and how the environment directly affects the way we move within a space. Which is sometimes tricky, because on-set often you’re in a studio, and you have to give somebody ideas of where they are so that they can imagine it. But if you’re working on location, the surroundings definitely affect how you move. The way the body reacts to architecture is very interesting for me. Once you notice it, it’s hard to unnotice. Being on the subway or the tube, for example – the structure is built for you to travel in a certain direction, or feel a certain thing. We don’t necessarily realise that until we switch it on. It’s often about having the talent switch that on.

How do you think the field will continue to evolve?

I’m hopeful that more brands will start exploring ways to make the live performance really interesting – in the same way that in the 1970s, you had designers working alongside artists on these shows that brought new eyes to the dance world. Chanel, for example, or Margiela, Rick Owens––a lot of these designers already understand the importance of it. You can live stream everything! Social media has turned us all into in-the-moment people.