For stylist Ian Bradley, fashion has always been personal—a way to see, archive, and celebrate identity. Raised just outside of Washington D.C., his formative years were shaped by styling his grandmother for church, curating wardrobes for Barbies, and soaking up inspiration in the galleries of the Smithsonian. That early training evolved into a dynamic styling practice spanning almost 20 years and a catalogue of work in T Magazine, L’Uomo Vogue, W, and campaigns with Saint Laurent and Thom Browne. Bradley’s styling is rooted in an innate cultural sensibility and an intuitive pulse on the zeitgeist. From styling Tumblr-era icon Sky Ferreira in the 2010s and creating editorials and campaigns with cultural tastemakers like Dev Hynes, Vashtie, and Luka Sabbat, to contributing to forward-thinking publications such as CANDY and Justsmile Magazine, perhaps his most notable collaboration has been with actor, model, and activist Indya Moore. Fresh off Moore’s national acclaim for their lead role in POSE on FX, Bradley and Moore curated a series of high fashion, high drama red-carpet moments from Iris van Herpen, Oscar de la Renta, and Louis Vuitton, alongside editorial and campaign work for Vogue España, Calvin Klein, and Louis Vuitton. With an eye trained in fine art, Black cultural reference, and a distinctly queer sensibility, Bradley’s work resists trends in favor of the everyday. Models.com contributor Shelton Boyd Griffith sat down with Bradley to talk about process, personal references, and the enduring power of subtle storytelling.

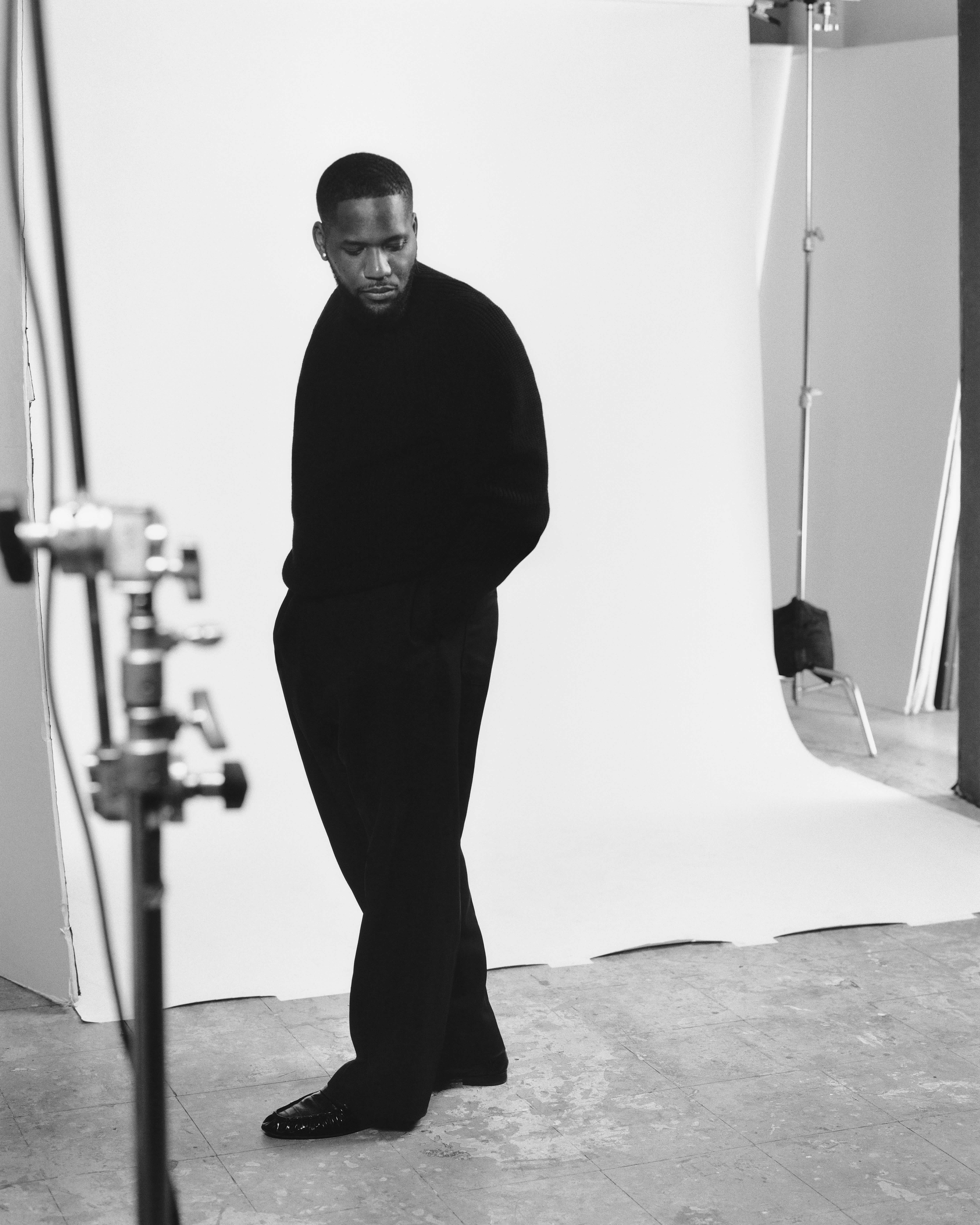

D’Angelo Lovell Williams for T: The New York Times Style Magazine | Image courtesy of Ian Bradley Studios

How did growing up in Virginia shape your point of view, style-wise or otherwise? Talk us through your fashion coming of age.

I always say my first two clients were Barbie and my grandmother. My grandmother was visually impaired, but she could still see color, so I would help her pick out her church outfits — you know, matching shoes, hat, suit, and bag. I’d even encourage her to try something a little different, like mixing patterns or colors. When I was younger, my babysitter would give me a box of Barbies, and I wouldn’t bother her for the rest of the night. Each time she babysat, she’d say, “Ooh, I got a new pack of shoes,” and I was all set. By middle school, I was really into fashion. I started following trends and getting Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, and my mom got me subscriptions to almost every fashion magazine. Living just outside of DC, I had access to the Smithsonian, so we’d go to fashion exhibits there. As early as sixth grade, we started coming to New York for spring break, where I saw more fashion exhibits and made my mom take me to fancy stores. The George Michael video for “Too Funky” was huge for me. Another fashion coming-of-age moment was seeing School Daze — a movie that really impacted me. The contrast between the Afrocentric kids and the scene with Tisha Campbell and Jasmine Guy singing in those flared dresses was very filling. Then Clueless really changed the game for me; that’s when I started to learn more about designers.

What’s currently fueling your creative eye?

Sonically, I’ve been really into Duval Timothy—really expressive, alternative jazz. That and Addison Rae. Dara [Allen] used to assist me, so her working with [Rae] has made me pay more attention. So, she’s hiring the right people and the music’s more complex than expected. Visually, I’m just always inspired by people I see on the street, and forever fascinated by people watching. I keep an ongoing note that I call a cheat, and it’ll be like, now it’s summer, so how a guy has the sweat towel draped over the head, I’m like, ‘wow, that feels kind of glamorous.’ Or the way a woman will be carrying, two tote bags and her purse. I’ve also really been into the craft of clothing right now, and just conceptually, how things are beautifully made, even if it’s the simplest thing.

What does your styling process look like, from concept to execution?

It starts with imagery. Being in this industry for 20 years, and doing it on my own for the last 10, I have my own root of inspiration, which I’m trying to challenge and constantly evolve from. With mood boards, it’s mainly to elicit notes of things I want to explore, textures, tones, and how they function as a means to communicate with the people I’m working with, to show what I’m thinking. However, it’s not necessarily my inspiration. Actually, once I send a mood board out, I don’t look at it. It’s just to communicate with my editor, the photographer, etc., because I don’t want to replicate things. I like the distortion of memory and what becomes of what I thought something was.

With over a decade in the industry, how have you seen it change?

For a majority of my assisting days, I used to be the only Black person on set and now I see more of us. So, that has been a really big shift, even post-BLM Movement. Even though I think the industry has regressed since then, I do see Black creatives in a much stronger placement than where it was when I started.

Your “Young, Queer, Gifted & Black” editorial for T Magazine is now considered a landmark moment in the Black LGBTQIA+ fashion canon. What did that project mean to you personally and professionally?

That project was huge for me. The concept was initially ideated by Shikeith. I had been following his work while he was still pursuing his MFA, and even before then. I draw a great deal of inspiration from fine art, sculpture, and performance mediums, which he navigates oh so well. I was truly honored to collaborate with him on this. It meant a lot because I became increasingly aware of how mood boards are often Eurocentric or attempts to replicate old-fashioned stories that don’t center us. Leading up to that project, I really committed to exploring my work through the lens of queer and Black identity, which was cathartic for me—showing myself, showing our beauty, and celebrating us. It felt like a culmination of ideas I’d been exploring for a long time. The artists involved were all people I’d already admired—some I had just met, but we remain in community and friendship. It was a complete creative experience, and I personally felt deeply fulfilled afterward, which isn’t always the case.

How does your approach shift when styling an editorial cover for, say, T Magazine versus a red carpet client or a campaign for a major house like Fendi?

With editorial, I get to really lead the direction. It’s exploring ideas that have been sitting in my brain and finding a way to merge them with the brief. Or sometimes the photographer comes to me with a concept, and I’m like, Okay, shooting in the streets of New York… how do we do that? Then I’m like, “Let’s do a cast of characters and this color story I’ve been obsessed with.” With talent dressing, it’s more of a service job. It’s about what makes them feel comfortable and their strongest, ready to go out there. I can have my ideas and try things, but it’s a collaboration, and we do what works for them.

Are there particular visual artists whose work you find especially compelling or influential?

I love portraiture painting and photography. Barkley Hendricks is literally my end-all be-all. It’s [Barkley’s work] literally in everything I do. What I like about it and what I aim to capture in my work is the beauty and regalness that can exist in an everyday person. That’s again what I like about admiring people in the street. They’re so special. Even if they’re wearing a hoodie and a durag, that just looks so beautiful and regal. I see that in the work of Barkley Hendricks, Amy Sherald, and Jamel Shabazz.

Is there a look or project from your career that felt like a breakthrough moment or turning point for you?

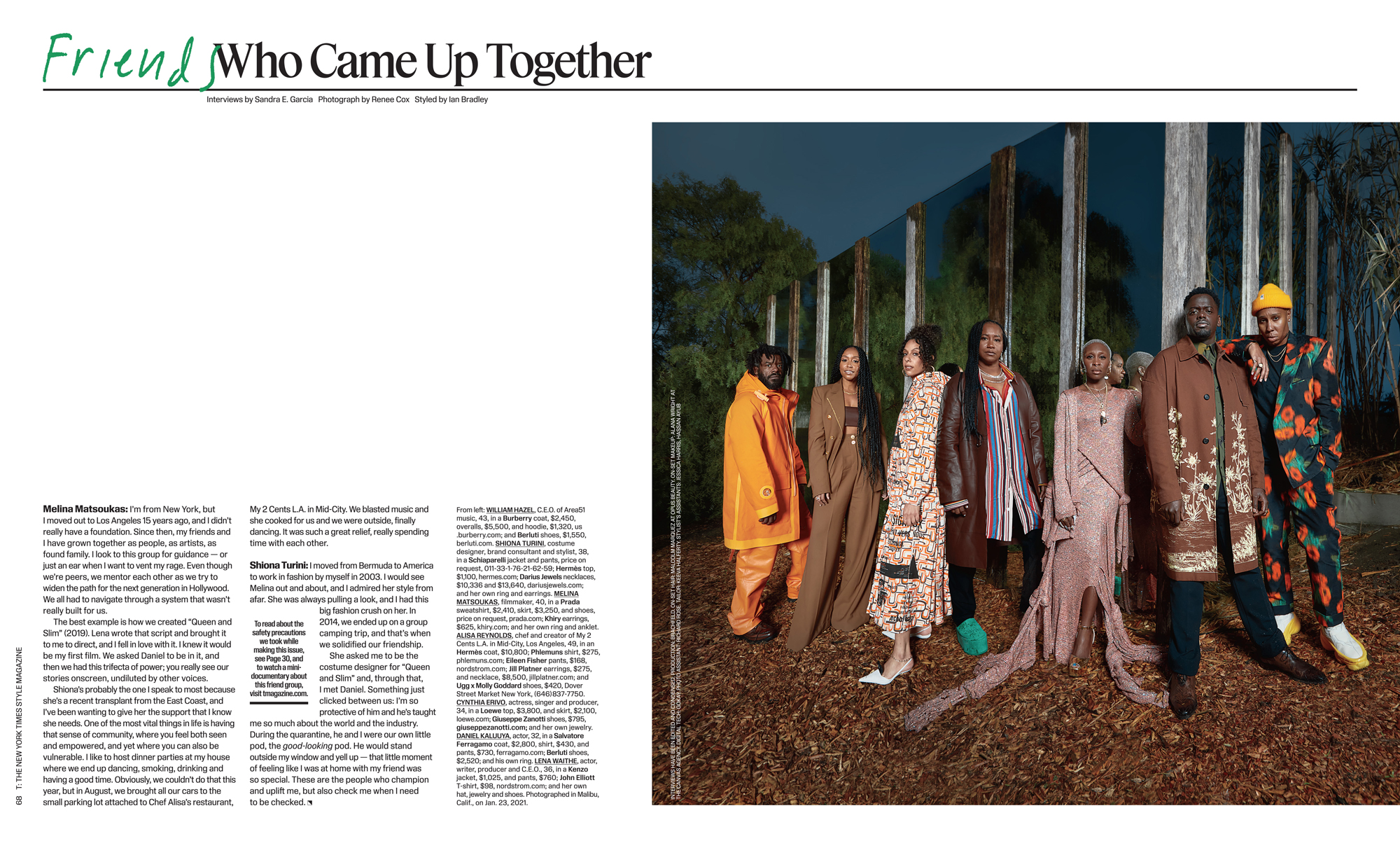

Working with Indya Moore was truly thrilling and also work that felt deeply important. When we did the Golden Globes, and Indya wore that silver mesh Louis Vuitton mini dress, collaborating with Nicolas [Ghesquière]’s team—my favorite designer of all time—was such a pivotal moment. It was really cool to bring an Afrofuturism vision to life with a brand like LV and someone like Indya, fully owning that space. Editorially, my first T Magazine cover, shot by Renée Cox and featuring Shiona [Turini], Melina [Matsoukas], Cynthia [Erivo], Lena [Waithe], and Daniel Kaluuya, also felt monumental—like a real shift.

What role does research—or even archival work—play in your process?

It plays a big part—like sourcing ideas from old imagery. I won’t necessarily take the clothing itself, but it might inspire a color palette, a placement, or even a gesture. And it’s never about replicating it exactly; it’s more about asking, “What is this energy?” I could be inspired by how someone wore something in the 1920s, then apply that same energy to a beanie and a sweatsuit. You might not even realize it, but it creates an entirely different way to wear something—one that people don’t always expect.

Any words of advice for any aspiring or emerging stylists?

You’ve got to be fully in it. Ten toes down. It’s all-consuming. The hours aren’t 9 to 5, but if you’re truly passionate about it, it can be deeply fulfilling. Define what matters most to you—work-wise, aesthetic-wise. It took me a while to figure that out for myself, but you have to let go of the “shoulds” and industry standards. Be aware of them, but don’t force yourself to do something just because another person is doing it, or because a certain magazine or model trend says so. Ask yourself: Who inspires you? Maybe everyone loves a particular designer right now, but if you don’t—and they’re not an advertiser—don’t do it. Find the people, designers, and aesthetics that genuinely move you, and define what you want to put out into the world.