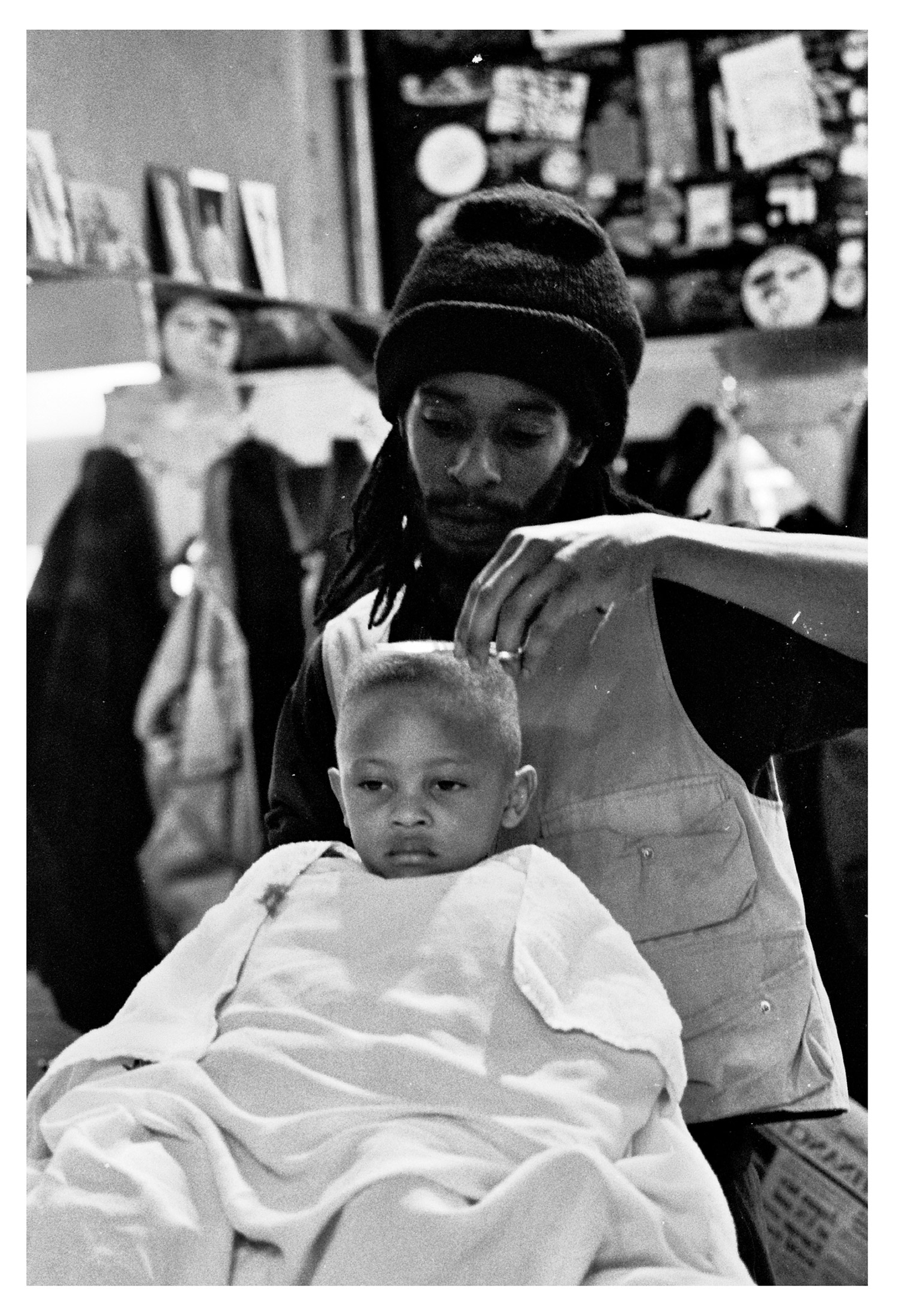

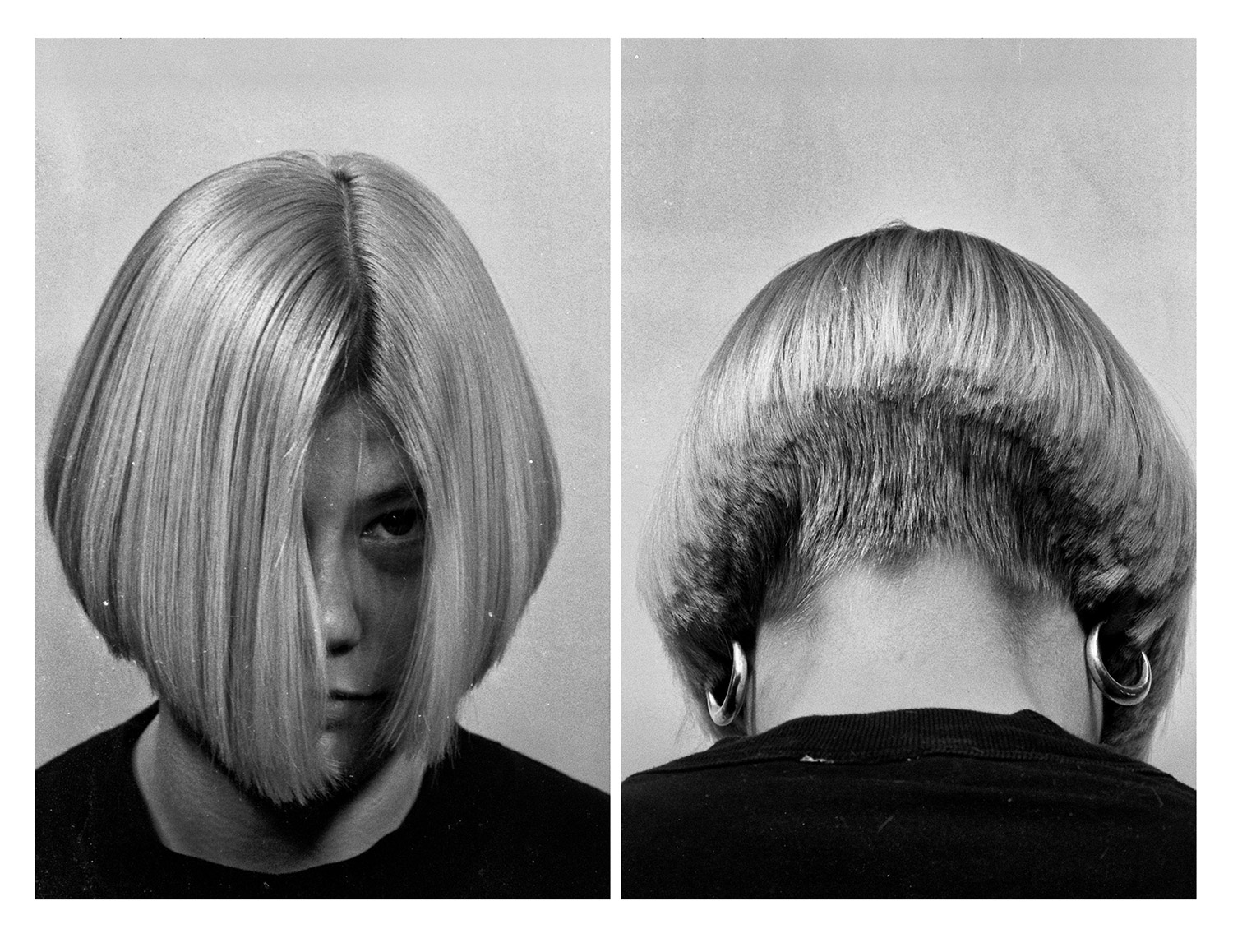

LEFT: Photo by Mark Lebon, RIGHT: Alice Temple by Norman Watson

It is possible you have never heard of Cuts, the cult hair destination for London’s creative crowd that, in its near 40 years, was a microcosm for the wave of Post-punks, Rockabillies, New Romantics and other subcultures pouring out of the 80’s bucking convention and needing a haircut to match the moment. Its walls have been permeated with the raw talents of its legendary clientele like Boy George, Bowie, 90s drum n’ bass star Goldie and colorful London somebodies and trendsetters––all freshly cut and stirring up the scene into something multicultural, alternative and uniquely of-the-moment.

Sarah Lewis’ film No Ifs or Buts, which just premiered at BFI London Film Festival, takes 20 years of documentation (yes, actually) and examines the cultural significance of that still-operating hair salon founded by James Lebon, brother of the photographer Mark Lebon (Tyrone’s father if the surname is familiar). Lewis began her filming in 1996 and continued on shooting inside the salon, often focusing on Steve Brooks who was James business partner and friend. She also rediscovered all-but-forgotten 35mm negatives: hundreds of portraits taken by Brooks in the basement of the shop, the contact sheets of which would be displayed in the window. Michael Kopelman of Gimme 5 knew Steve’s images were precious, so Mark Lebon took the Cuts’ ephemera and edited it into a 500 page book titled CUTS published by Gimme 5 and DoBeDo. Together, No Ifs or Buts and CUTS intimately map the hair salon’s rich past against modern times. We spoke to both Sarah and Steve in order to celebrate the debut of the film and the book

No Ifs of Buts was produced by Nic Tuft. For more information on the film, visit its website at www.noifsorbuts.co.uk

After working on this project for so long, how does it feel finally giving this documentary an audience?

I actually feel relieved. Even when I wasn’t working on the film I still lived with it in my life, I wanted to finish it for all the love, time and energy that had gone into the making of it over so many years. It also represents a time that was pre-social-media which no longer exists and I think that is fascinating to have a window into, especially for younger people who have always lived with mobile phones.

How much did you know going into the project about the subcultures and lifestyles that Cuts was in the center of?

Before I had been to Cuts, I had just heard about what an amazing place it was, how it attracted such a vibrant creative community and this is what we were interested in documenting. I didn’t understand the history of Cuts at this stage and how it spanned 20 years when we first started filming there in 1996. It now still exists as ‘We Are Cuts’ in Soho and has been going 40 years.

How rare do you think micro-hubs of creative society and genuine DIY culture like Cuts have become?

With the advent of social media came the belief that living lives through mobile phones has somehow replaced the need to have places like Cuts where people go not necessarily to have a haircut but more as a place to connect with others and meet up with people in a physical space. I’m not sure if this still exists in the same way with youth culture today, but it used to be a necessity––if you wanted to meet people you had to go and physically spend time with them and this is what Cuts cultivated.

When did you rediscover Steve’s photos? How did they become the book from there?

I first knew about Steve’s photos when he took some images of me. He always shot the images in the basement downstairs and the way he worked was very organic and unstructured. He then displayed the photos of Cuts’ clientele, friends and family in the shop window so they became part of the whole Cuts’ vibe. I must say he didn’t exactly archive the negatives in a professional way so as we were making the film, I started to collect the negatives. I then took them back to Australia with me. Michael Kopelman from Gimme 5, who’s a long-term friend of Cuts, saw the shots and then Mark Lebon took on the task of editing them into the beautiful book that we have today.

What customers and patrons defined Cuts and made it special? What similarities do you think they shared?

There was a real mixture of famous people alongside regular punters––you never knew who you’d wind up sitting next to on the bench out the front. People like Goldie, Fran from Travis and Keith from Prodigy would share the space with regular punters. It was a well-known place but very low-key in some other ways. No one was ever made a fuss over.

Considering the span of time you filmed when did you have a clear vision of the story you wanted to tell in the documentary?

It started out as an observational documentary, we would just turn up at Cuts with our crew and try and just see what we could capture on the day. It was random but we wanted the energy of the place to tell us the story. I tried to create a narrative from the footage but it is only when we went back in time later that the narrative started to build. It became about James Lebon, who first started Cuts and his friendship with Steve Brooks. Steve’s story is the driving force, he was the one who gave so much of himself in the making of the film. He made himself vulnerable and exposed a side to being human that most people keep hidden, this is what engages the audience and makes the story more of a universal one outside the confines of the Cuts. It’s like working on a big complex jigsaw puzzle and it feels so great when it all started to make sense.

Did you ever get your hair cut there while filming? Can you ever look at hair in the same way?

When I started filming at Cuts I had shoulder length blonde hair, a very “normal” haircut. Over the 2 years that we were filming there I had all my hair cut off into a very short pixie hairstyle, which I loved. I then dyed it red and had a tiny mohican style on top with long bits down the side; I don’t have a name for the haircut, I think they just tried things out with different clients. Luckily, I was often there as short hairstyles are a lot more difficult to maintain. It really opened up the possibility of exploring what suited. Now I understand how good stylists work with their clients individually to create a unique look that suits that person, it can be a bit like sculpture.

Can you explain the process of taking those pictures featured in the books? Why did you start doing it?

There was nothing that strategic about it, it just came out of the energy of the shop. I had access to a camera and really interesting beautiful people came through the doors so it came from that. It was also something to do with suppressed sexual drive, boredom, creativity and a record of the time. I used to pin the images up in the windows and it was nice for the clients to see themselves mirrored back in this way.

How was having Sarah in the shop and her working on this project over so many years?

It took many forms over the decades. At first, she was just documenting the Cuts shop and I suppose trying to find a story, but as time went on it became more intense and intimate which was also difficult for me. It was easy to play the fool and act cool and wear a mask but was horrible when it became really real.

Cuts was a cultural petri dish––did you always know it was something special in that way or did it come when looking back?

No, it was just my normal. It was all I knew. It was like my front room and people were there. It was also a gilded prison, as there came a time when I needed to leave for my own growth. It was impossible to leave and yet difficult to stay.

What were a few of the most important changes the shop went through over the years? What were some of the biggest challenges of running it?

The shop changed location quite a few times and is still going today in Dean Street, Soho. I remember when we started doing dreadlocks working with really new techniques, that would have been early 80’s––about ’82. But then I stopped doing that as I felt that white people were wearing them without acknowledging the price of what being a black racial minority meant. I loved the whole New Romantic movement in the 80’s but then embraced the new black music: R&B, Motown, soul music and loved reggae. I wanted to acknowledge black music influence in music and lifestyle but didn’t want to appropriate it. The people who came into the shop affected the energy of the place and then what came out of those interactions influenced fashion and media through the people who came in. It was challenging for me having to create a boundary between my fellow workers because I had to be the boss and yet I desperately wanted to be friends. I loved the chaos but if I wasn’t the order then everything fell apart.

What clientele defined Cuts? What particularly were they attracted to and why was it such a port for creatives?

Like attracts like. It was word of mouth and we never knew who would come through those doors. Goldie was working on a film with David Bowie so he told him about us and then Bowie popped by to get his hair cut. But most of the time we never knew why exactly people came in. With a 40 year history there’s a huge amount of London based people who have had their hair cut there including Neneh Cherry, Sean Penn, Jean Paul Gaultier, David Bowie, Michael Hutchence, Simon Lebon, Steve McQueen, Alexander McQueen, Chris Ofili, Beastie Boys, Roy Ayers, Jeff Beck, Davina McCall, Bianca Jagger, Lenny Henry, Ant & Dec, Rupert Everett, Sacha Baron Cohen, William Orbit, Guy Richie, Will Self, Simon Fuller.